- Home

- English

- Structure of the Bible

- Structure of the Menorah

- Ancient Menorahs

- Calendar and Feasts

- Resurrection on Sabbath

- Introduction

- Day

- Sabbath

- High Sabbath

- Pre-Sabbath

- Week

- Interlinear Bible

- Church Opinions

- 1. No Sunday

- 2. A Sabbath

- 3. No Friday

- 4. Intermediate Day

- 5. Three Days and Three Nights

- 6. Manipulations

- 6.1 Sabbath not Sunday

- 6.2 Plural σαββατων not week

- 6.3 one not first

- 6.5 Day of the Sabbaths

- 6.7 Lords Day

- 7. Old Bibles

- Greek Bibles

- Latin Bibles

- Gothic Bible

- English Manuscripts

- English Bible Prints 1

- English Bible Prints 2

- English Bible Prints 3

- English Bible Prints 4

- German Manuscripts

- German Bible Prints 1

- German Bible Prints 2

- Spanish Bibles

- Italian Bibles

- Swedish Bibles

- Czech Bibles

- μια των σαββατων

- Mt 28-1

- Mk 16-2

- Mk 16-9

- Lk 24-1

- John 20-1

- John 20-19

- Acts 20-7

- 1Cor 16-2

- Lk 18-12

- 7 Languages

- Palm Sabbath

- Omer

- Summary

- The Rapture

- Rabbi Kaduri Note

- 666

- 888

- Video

- Info

- Historic Bibles Facsimiles

- Francais

- Deutsch

- Espanol

- Dutch

- Ελληνική

- Pусский

- Introduction

- Day

- Sabbath

- High Sabbath

- Pre-Sabbath

- Week

- Interlinear Bible

- Church Opinions

- 1. No Sunday

- 2. A Sabbath

- 3. No Friday

- 4. Intermediate Day

- 5. Three Days and Three Nights

- 6. Manipulations

- 6.1 Sabbath not Sunday

- 6.2 Plural σαββατων not week

- 6.3 one not first

- 6.5 Day of the Sabbaths

- 6.7 Lords Day

- 7. Old Bibles

- Greek Bibles

- Latin Bibles

- Gothic Bible

- English Manuscripts

- English Bible Prints 1

- English Bible Prints 2

- English Bible Prints 3

- English Bible Prints 4

- German Manuscripts

- German Bible Prints 1

- German Bible Prints 2

- Spanish Bibles

- Italian Bibles

- Swedish Bibles

- Czech Bibles

- μια των σαββατων

- Mt 28-1

- Mk 16-2

- Mk 16-9

- Lk 24-1

- John 20-1

- John 20-19

- Acts 20-7

- 1Cor 16-2

- Lk 18-12

- 7 Languages

- Palm Sabbath

- Omer

- Summary

English Bible Prints to 1799 and the Sabbath Resurrection

As with the English manuscripts, there are also numerous printed Bibles that speak of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath". The German manuscripts, which were all Catholic Bibles, even speak of the women coming to the tomb "on a Saturday" morning. The English language does not offer the variety in number and content that German Bibles do (see Historic Bibles). Also, the first Bible society in the world (Cansteinsche Bibelanstalt; 1710) was founded in Germany and was even the only one in the 18th century. The first English Bible Society was founded only 100 years later (more precisely in 1804). For several centuries Germany was the most important country in the spread of the Gospel. However, this changed after the First World War, when English-language Bibles were increasingly produced. Since letterpress printing was invented in Germany (Mainz), printing presses were transported all over Europe. But the state and the church were often against the distribution of the Word of God in the national language, because personal interests were often in the foreground. That is why the first English Bible printings were done secretly. While the first two English printed Bibles still had inaccuracies in the resurrection chapter (in contrast to the English manuscripts), the following Bibles were much better, e.g. the Coverdale Bible 1535. The German Bibles were much more accurate on this point (because the German language knows the genitive case, which was often used in the Greek NT); especially the Luther Bible, until the revision around 1900, proclaimed the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" and His appearance to the disciples "in the evening of the same Sabbath" (John 20:19).

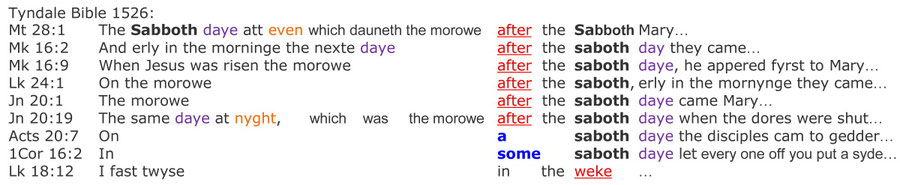

Tyndale Bible 1526

The history of printed English Bibles did not begin in England, but in Germany and Belgium. In 1525/26, William Tyndale (*1484, †1536), who had fled church persecution from England to Germany, translated the NT into English and had it printed in Worms (info and facsimiles). With this he aroused the wrath of the English King Henry VIII. (*1491, †1547) and the English Church, which at first was still connected with Rome and only allowed the Vulgate. Therefore Tyndale was condemned to death at the stake. Although he did not travel back to his homeland, he was nevertheless strangled in Belgium in 1536 and burned at the stake. Most of his Bibles were also burned. The only completely preserved copy of the first print (Worms 1526) is now in the Württembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart (Germany, Link). Tyndale did mention the word "Sabbath," but since he had learned the Sunday resurrection of Jesus since his childhood, he added the word "after" to the Bible, although it is not found in the basic Greek text, nor in the Vulgate (see Interlinear Bible). The evangelists speak at all places of an event "on a Sabbath day" and not "after a Sabbath day". Important: In Acts 20:7 there is exactly the same phrase "μια των σαββατων" (see Link; Latin: una autem sabbati) as in Mk 16:2; Lk 24:1 and Jn 20:1. But Tyndale has only translated Acts 20:7 correctly and has added the word "after" in the other passages without any reason. Tyndale did not understand the expression "first Sabbath" in Mk 16:9, which is mentioned in the Greek basic text, either, and even here he replaced the word first (Latin: prima; Greek: prote) by "after". However, his forbidden translation work was not in vain, for it also served as the basis for the King James Bible of 1611. After more than 300 years, the Tyndale Bible was also reprinted in England by Samuel Bagster in London. Also the editions of the years 1836 (London), 1837 (New York) and 1862 (Bristol) contain the same text of the Tyndale Bible of 1526 and testify the gathering with breaking of bread and the collection "on a Sabbath":

Note: In some computer programs, Acts 20:7 and 1Cor 16:2 say "after the sabbath". This is a modern change to remove the reader from the Sabbath, for in the original of 1526 and in various reprints (even e.g. 1884) there is talk of "on a saboth daye". That is a big difference. Already in 1534 and 1552, i.e. 16 years after Tyndale's death, some revised texts of the Tyndale Bible appeared, in which the breaking of bread continued to take place "on one of the Sabbath days", but the collection was postponed to a Sunday:

Joye Bible 1534

George Joye (*1495, †1553) initially assisted William Tyndale with his Bible translation. From 1530 he began to translate individual books of the OT into English himself. In 1534 his NT was published, which in most places hardly differs from Tyndale's edition (info and facsimiles). Here too it becomes clear that the Resurrection Sabbath should be removed from the Bible in accordance with church doctrine, for in Acts 20:7 he translates "μια των σαββατων" or "in una sabbati" (the Latin translation of the Vulgate) quite correctly as "on a saboth daye". But quite exactly the same three Greek and Latin words are also found in the basic text at Mk 16:2; Lk 24:1 and Jn 20:1, so it becomes obvious that he deliberately added "after" and "nexte day after" (Mk 16:2) in his Bible translation, contrary to the Greek basic text and contrary to the Vulgate, in order to justify Sunday sanctification and to erase the resurrection Sabbath:

Coverdale Bible 1535

Miles Coverdale (*1488, †1569) produced the first full Bible in English in Antwerp (info and facsimiles; BIBLIA The Bible / that is, the holy Scripture of the Olde and New Testament, faithfully and truly translated out of Douche and Latyn in to Englishe). The Vulgate as well as the Tyndale and Luther Bible served as the textual basis. In all places Coverdale was able to translate the content of the Vulgate very well. He was able to separate the words "first" and "a/one" and spoke of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning". Coverdale's translation was a marked improvement as it was much more accurate than those of Tyndale and Joye. He never mentioned the word "after" in the resurrection chapter. Even in 1838 and 1847 this Bible was reprinted in London by Samuel Bagster with the text unchanged. This means that English-speaking Christians could learn of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" and on the "first day of the Sabbaths". But as many Christians were not interested in God's calendar, they could not know that in Mk 16:9 not the "first day of the week" was meant, but the first of the seven Sabbath days up to Pentecost. Coverdale was (unlike some theologians and pastors today) an outstanding translator, a master. In John 20:19 he speaks of the "same Sabbath" (not same Sunday), which every English child understands:

Matthew Bible 1537/1549

The name of the Bible translator Thomas Matthew is a pseudonym for John Rogers (*1500, †1555), a friend of Tyndale (see info and facsimiles). He published the forbidden text of Tyndale under a false name and completed it in some parts of the Old Testament with the text from Coverdale. During the reign of Queen Mary, Rogers was burned alive in 1555. He was one of the first Protestant martyrs in England. In terms of content, the text was a great deterioration, for Acts 20:7 says "the morrow after the Sabbath" and in 1Cor 16:2 even "Upon some sonday". The Taverners Bible of 1539/51 by Richard Taverner (*1505, †1575) is a slightly revised printed edition of the Matthew Bible, which consequently also contains the Sunday in 1Cor 16:2. So far, no one has found the word "after" in these sentences in the basic Greek texts or the Latin translation. It is a sin to make such additions to the Bible, because God speaks of the Sabbath 7 times, while Sunday was not mentioned once in the whole Bible because it has no place here. If God had meant Sunday, He would have said it. There are numerous possibilities for this in ancient Greek (see No Sunday).

Hollybush NT 1538

John Hollybush (or a pseudonym for Coverdale?) showed the Latin text of the Vulgate and next to it the English translation (info und facsimiles). This work is reminiscent of that of Coverdale in 1535, but is not as accurate and contains a major error in Lk 24:1. The Evangelist Luke certainly did not write the word "after", because according to the Latin translation he said "una autem sabbati" (but on a Sabbath), which are 100% the same words as in John 20:1 and Acts 20:7. As can be clearly seen, the translation of the Vulgate is inaccurate, only in Mark 16:2 and 1Cor 16:2 the word "one" was correctly translated. Nevertheless this translation is important, because it also proclaims the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath". In terms of content it is not important whether it is spoken of "a Sabbath" (literal translation) or the "first Sabbath day" or the "first day of the Sabbath(s)" or "first of the Sabbaths", because it was meant to be the first of the 7 weekly Sabbaths between Passover (Nisan 15) until Pentecost (the 50th day after 7 weekly Sabbaths).

Great Bible = Cranmer Bible 1539/40

The first editions were printed in Paris (Francis Regnault) and London (Edward Whitchurch; J. Cawood) ("The Byble in Englyshe that is to saye the content of all the holy scrypture, both of ye olde and newe testament, truly translated after the veryte of the Hebrue and Greke textes, by ye dylygent studye of dyuerse excellent learned men, expert in the forsayde tonges"; see info and facsimiles). This Bible was intended for the Church of England and had the inscription "This is the Byble apoynted to the use of the churches" on the title page. Because of its large format, it was also called the "Great-Bible". King Henry VIII. (Henry, *1491, †1547) personally, hereby issued the first official (authorized) Bible in English to replace all previous ones. The first version was published in London and Paris in 1539, the second in 1540 ("The Byble in Englyshe, that is to saye the contet of al the holy scrypture both of ye olde, and newe testament"). Until 1541 there were 6 editions. By order of the king, every church and cathedral had to buy one copy. The title page shows not Jesus or the Pope, but King Henry handing over the Word of God to the translator, the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer (*1489, †1556), and the highest minister of state Thomas Cromwell (*1485, †1540) and thus spreading it. Cranmer had won the King's favour by supporting his divorce from Catherine of Aragon and by validating Henry's new marriage to Anne Boleyn. This, however, led to a break with the Catholic Church of Rome, resulting in the creation of the new Anglican Church, which even threatened war with the Catholic countries. After the death of Henry, Queen Mary I Tudor (Bloody Mary; *1516; †1558) came to power. Since she was Catholic, she had Cranmer and other Anglican bishops burned at the stake in 1556 and forbade the use of the Great Bible. Important fact is: Neither the English King Henry VIII nor the English Church had a problem with the biblical resurrection of Jesus on the Sabbath, because the translation basis (Vulgate) itself says the same. Therefore, all Christians have been able to find the resurrection of Jesus "on the first Sabbath" in this first official main Bible of the English churches, even though the church officially preached a resurrection on "the first day of the week". Had Cranmer (except in Mk 16:9) avoided the word "first" and translated the Latin una (one, a) instead, as he did in Acts 20:7, his Bible would be even more accurate. The expression "day of the Sabbaths" is in the ancient Greek language a well-known term for the Sabbath in the singular (see Interlinear). The original text of the Cranmer Bible was also contained in the Hexapla of 1841, a book in which six English editions of the Bible were compared verse by verse (see Polyglot Bibles). This Bible was truly a "Great Bible" because it describes the resurrection of Jesus on the first of the seven Sabbaths until Pentecost. But only those who know the calendar of God described in the Old Testament (Lev 23) can understand what is meant. The others begin to interpret. Only in Mk 16:9 was the word "after" added to the Bible, since verse 1 speaks of the time after the Sabbath. It was not logical for the author, since he did not know that there are three Sabbaths during the Passover feast and seven until Pentecost.

Coverdale Zurich Bible 1550

The NT of Coverdale was reprinted in Switzerland (Zurich). However, the title "The newe testament faythfully translated by Miles Coverdal, Anno 1550" is misleading, because this is not the original, but a version modified by Protestant theologians (see info and facsimiles). In this version the word "after" was inserted in all sentences, so that a completely different meaning was created. The text corresponds more to the translation by Tyndale and follows the Matthew Bible. As shown by the revised edition reprinted in London in 1553 and also by the late prints of 1838 and 1847, Coverdale always spoke of "a Sabbath" and never of the day after the Sabbath. In the Bible printed in Switzerland, 1 Corinthians 16:2 even speaks of Sunday, which is a brazen distortion of Coverdale's translation ("Upon some Sabbath") and the Word of God.

Coverdale Bible - Revised Edition 1553

Coverdale Bible, revised edition of 1553 (info and facsimiles): Also the last edition, which was printed in 1553 in London by Rycharde Jugge, contains a revised spelling, but still speaks of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath", as especially in Lk 24:1 and Jn 20:19 clearly shows:

Geneva Bible 1557/1560

When Mary I. Tudor (*1516; †1558) became Queen of England and Ireland from 1553 to 1558, she attempted to reintroduce Catholicism as the state religion. As a deterrent she had over 300 Protestants killed, which earned her the nickname "Bloody Mary". English Bibles were banned, only the Latin Vulgate was allowed. Several Protestant refugees who had fled England found a new home in Switzerland and printed the New Testament in 1557 in English and the complete Bible in Geneva in 1560 (see website info and facsimiles). It was the first English Bible to be translated from Hebrew and Greek. It was also the first Bible that had not only chapters but also vers numbers. It was also rich in commentary. John Calvin, John Knox, Myles Coverdale and John Foxe were involved in this work. At great personal risk the Bible was finally smuggled to England. Due to its handy format, the Geneva Bible was a real house Bible. It was the Bible that Shakespeare (†1616) quoted in his works. Because of the use of the word "breeches" (trousers; in Gen 3:7), the Bible was nicknamed "Breeches-Bible". The printed version of 1599 was used by the pilgrims who emigrated to the USA in 1620, which is why it was also called the "Pilgrim Bible". It served as a translation basis for the first Bible printed on the American continent (Eliot Bible 1663 in the language of the Indians). The Geneva Bible was replaced by the King James Bible in 1611 only after 50 years. As a Protestant translation, it is based on the French "Bible de Genève 1551" by Calvin and the revised Tyndale Bible of 1552, but in some places it was freer and less precise, and therefore speaks of the "first day of the week". In a marginal note to Acts 20:7 the Geneva Bible even goes so far as to add a disastrous explanation:

“The first day after the Sabbath which we call Sonday. Of this place & also of the 1. Cor. 16:2 we gather that the Christians used to haue their solemne assebles this day. laying a syde the ceremonie of the Jeweshe Sabbath“.

However, the translators only came to this conclusion because they were guided by church doctrine and not by the Greek or Latin text of the Bible. While Tyndale at least still mentioned the Sabbath in all passages and stated the meeting of Christians "on a Sabbath day", the word "Sabbath" in the Protestant Geneva Bible has now completely disappeared in the most important passages.

Théodore de Bèze (also Theodore of Beza; b. 1519; †1605) adopted the text of the Geneva Bible in 1599, making only minor changes:

Bishop's Bible 1568

After the death of Queen Mary I (Bloody Mary; *1516; †1558), who wanted to destroy all English Bibles, some Anglican bishops began to revise the Great Bible of 1539 with the aim of replacing the Bibles smuggled into England and inaccurately translated. Although the Greek text served as the basis for the revision, a connection with the Vulgate is nevertheless evident. The main translator was the Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker (*1504, †1575), who had "The holie Bible conteynyng the olde Testament and the newe" printed in London (info and facsimiles). It was the Bible translation authorized by the newly founded Anglican Church of England and was given the name "Bishop's Bible". Also in this edition the faithful could read that the Christians met "on one of the Sabbath" and that Jesus rose from the dead "on the first day of the Sabbaths", although Mt 28:1b and Mk 16:9 are reported from the day after. For every connoisseur of the Septuagint it is clear that with the Greek "day of the Sabbaths" only a single Sabbath day could be meant and no day after that (more info). The Christians were told, however, that Sabbothes (Sabbaths) could allegedly also mean "weeks". To support this false doctrine, "one" was replaced by "first" (correct only in Mark 16:9) and the word "day" was added. In addition, in Mk 16:2 the terrible marginal note "This is Sunday, the first day of the week" was added so that the faithful would refrain from the Sabbath. But Acts 20:7 has exactly the same sequence of words in the original text as in Mk 16:2; Lk 24:1 and Jn 20:1, namely "one of the Sabbaths" (μια των σαββατων). So it becomes clear that also the other verses could have been translated correctly, if it had really been intended:

Tymme's Calvin Commentary as of 1570

Augustin Marlorat (*1506, †1562) and especially John Calvin (*1509, †1564) have written French Bible commentaries, which after about 30 years were translated into English by Thomas Tymme (Timme; †1620) and others ("Written by M. Iohn Caluin: and translated out of Latine into Englishe by Thomas Timme minister"; info and facsimiles). Tymme worked correctly, but already in 1584 (Fetherstone) and 1610 the Calvin commentary appeared in London (Thomas Dawson), in which the week was introduced in all places (except Jn 20:1,19). The Calvin Translation Society, however, reintroduced the Sabbath in 1847 (Rev. Pringle). Calvin usually spoke of "le premier jour des Sabbaths" (the first day of the Sabbaths) in his translation, but in his comments he admits that "μίαν" should actually be translated as "one". Of course Calvin wanted to lead people away from the Sabbath, so he claimed that the evangelists supposedly meant "on the first day of the week" or "after the Sabbath. In fact, in terms of content it is not important whether "on one" or "on the first of the Sabbaths" (as Mk 16:9 in the Greek basic text literally means) is spoken, but the Sabbath must be mentioned. For it is always only "the one of the" three Sabbaths during the Passover feast that is at issue, or even more precisely the "first of the Sabbaths", namely the first of the seven Sabbaths up to Pentecost. But this can only be understood by someone who is familiar with the calendar of God, otherwise he can never understand why Mk 16:1 and Lk 23:56 speak of a period AFTER the Sabbath and why the women came to the tomb again "on a Sabbath":

Wessex Gospels according to Fox 1571

In 1571 John Fox (*1516, †1587) and Matthew Parker (*1504, †1575) published the Wessex text in London in two columns, namely the West Saxon Gospels 990 and next to it the text of the Bishop's Bible 1539 ("The gospels of the fower Euangelistes: translated in the olde Saxons tyme out of Latin in the vulgare toung of the Saxons"; see facsimiles). In both versions the resurrection of Jesus took place "on a Sabbath morning" (see English manuscripts). But the 550 years older Wessex version is much better, because it translates the Vulgate much more accurately; it avoids adding the words "week" and "after". It can also distinguish very well between one (anon) and first (forman). Although this Bible has adopted the error of Jerome in Mt 28:1b, the text has otherwise always been translated excellently. Above are the extracts of the most important word comparisons with translation.

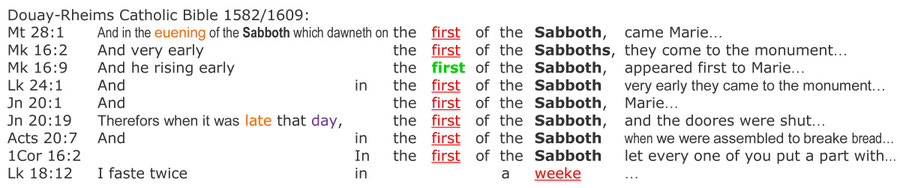

Douay-Rheims Bible 1582/1609

The Catholics from England (Oxford) wanted to strictly distance themselves from the Anglican Church. They decided to emigrate to the mother church on the European mainland. In France they founded an English college and began to produce the first official English Catholic Bible (info and facsimiles). Of course, the catholic Vulgate served as the textual basis. The translators were Gregory Martin (*1542, †1582), the Cardinal William Allen, Dr. Stapleton, Rich. Bristow and Thomas Worthington, from whom the footnotes were taken. The NT was printed in 1582 by John Fogny at the English College of Rhemes (Rheims) in France (Rheims New Testament; "The New Testament of Jesus Christ, translated faithfully into English, out of the authentical Latin, according to the best corrected copies of the same"). In 1609 the OT was also printed in the English College of Douay (University of Douai); the complete edition was therefore called Douay-Rheims Bible (or Douai-Rheims Bible). This Catholic Bible was reprinted in 1633 by Iohn Covstvrier, more than 70 years after the Geneva Bible of 1557 and more than 20 years after the printing of the King James Bible of 1611. In 1872 it was even reprinted in England (London) by Samuel Bagster. It is a valuable bilingual version, containing on one side the Latin Vulgate and on the other the English text of 1582. While the King James Bible 1611 and the Protestant Geneva Bible 1557 spoke of the Sunday Resurrection of Jesus, the Catholic Douay Rhyme Bible retained the Sabbath Resurrection up to the editions printed around 1900. The original translation with the text from 1582 was reprinted in 1834 by Catholics also in the USA (New York, see facsimiles). The translators of the English version made a few mistakes in not always rendering the words of Jerome as accurately as he meant them, and in all places they spoke of the first (prima) instead of a (una) Sabbath. But this Catholic translation is significant because it proves that the Latin Vulgate (which is a translation of the original Greek texts) speaks of an event "on a Sabbath morning" (una sabbati), namely "on the first of the Sabbaths", that is to say, the first of the seven Sabbaths up to Pentecost and of no other day. By contrast, the footnotes in the Bible are often disastrous, for there it is claimed that "on the first of the Sabbaths" is supposed to mean "on the first day of the week" or "on a Sunday". According to Leviticus 23, there are exactly 7 Sabbaths (7x7=49 days) that must be counted until Pentecost (50th day). And if there is a seventh Sabbath, then of course there must be a first Sabbath of this series mentioned by the evangelists. What is difficult to understand about this, especially since there are completely different Greek and Latin words for the week (see week)? How else would God have had to express it in ancient Greek if He really meant the "first of the Sabbaths"? This is so easy to understand:

The text of the 1834 edition, reprinted in New York, continues to proclaim the resurrection of Jesus on the "first of the [seven] Sabbaths". This is absolutely correct, because it is in fact the first of a series of 7 Sabbaths until Pentecost, which are counted every year until today. Similarly, Catholics count the 4 Sundays of Advent to Christmas, starting with the "first of the Sundays" and ending with Christmas. So also the Hebrews counted the 7 Sabbaths. Anyone who takes the OT seriously and knows the calendar of God understands this.

Revised Douay-Rheims Bible (American Edition): The Catholic Bishop Dr. Richard Challoner (*1691, †1781) from England carried out a revision as early as 1749, in which he replaced the Sabbath with the "first day of the week" (see facsimiles and the Bible of the US Presidents). His Bible became the standard for all English speaking Catholics. The Douay-Rheims Bible, revised by Richard Challoner, was printed in 1790 by Matthew Carey (1760-1839, Carey Bible) in Philadelphia (USA; Carey Bible). So there were several American Catholic Bibles in circulation at the same time, sometimes talking about the Sabbath resurrection and sometimes about the Sunday resurrection of Jesus, so that there was a certain confusion. Although it was said that the expression "first of the Sabbaths" meant Sunday, this was not logical, since there is only one "first Sabbath" in God's calendar, namely the first weekly Sabbath after the Passover High Sabbath (15th Nisan). The following is the text of the Douay Rheims American Edition of 1899:

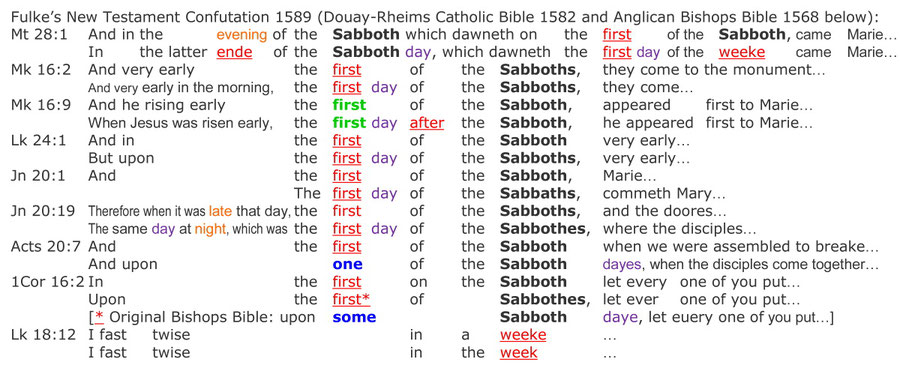

Fulke’s New Testament Confutation 1589

Already shortly after the publication of the Douay-Rheims Bible of 1582, comparative two-column translations were printed in London over many years, showing on the one hand the text of the Catholic Douay-Rheims Bible produced in France ("The Translation of Rhemes") and on the other hand that of the translation of the Anglican Church of England ("The Translation of the Church of England"; see info and facsimiles). By the latter, the Anglican Bishops Bible 1568 was meant. The most important work on this was done by William Fulke (*1538, †1589). He placed the Catholic (translated from the Vulgate) side by side with an Anglican translation of the NT (translated from Greek; the text corresponds for the most part to the revised Bishops Bible). He wanted to point out the errors in the Catholic edition. But instead he shows that the Catholic version was better in some verses (e.g. Mt 28:1a; Mk 16:9). Like many Christians today, Fulke did not know the calendar of God. So he could not know that the expression "first of the Sabbaths" or "first day of the Sabbaths" did not mean the "first Sunday", but the first of the seven Sabbaths up to Pentecost. In order to dissuade Christians from this biblical truth, he added useless marginal notes in which he said that the resurrection of Jesus allegedly took place on "Dies Dominica" ("Sunday, Lord's Day"). This is of course nonsense, because otherwise no one could say "on one of the Sabbaths" or "on the first of the [seven] Sabbaths" in ancient Greek and ancient Latin, since it would automatically always have to mean "on a Sunday". Dramatic is the comparison of both Bibles in Mk 16:9 by the addition of the word "after", which gives rise to a completely different meaning. Moreover, even the Vulgate never mentions the Dies Dominica (Lord's Day), so his comments turn out to be a Christian seduction. Fulke also failed to notice that both Bibles do not distinguish between prote (first) and mia (a/one). But no matter what Fulke writes in his marginal notes, a Christian who knows the calendar of God knows that both Bibles nevertheless report of the resurrection of Jesus "early on the first Sabbath" (Mk 16:9):

Both Bible versions used either the Vulgate (Douay-Rheims) or the basic Greek text (Bishops Bible), but came to the same conclusion independently of each other. The Catholic and Anglican versions almost always mention the Sabbath. According to the biblical calendar, the expression "on the first Sabbath" or "on the first of the Sabbaths" never meant Sunday, but always only the first of the seven weekly Sabbaths, which were counted every year until Pentecost and are counted up to the present day and also in the future. Everyone understands that. But the different churches wanted to part with the hated Sabbath, so they were forced to reinterpret their correct Bible texts, at least in the marginal notes. In Mt 28:1 and Mk 16:9 the Catholic Bible is even more precise, because it has omitted the words "week" and "after". But in 1Cor 16:2 the "Fulke New Testament Confutation" does not contain the original text of the Bishops' Bible, for it speaks quite correctly of "upon some Sabboth daye". But this is exactly the message that the makers of the Bible wanted to hide from the Christian readers. The following image shows the text of the Vulgate, the Douay-Rheims Bible 1582 and the original Bishops' Bible 1568 (below):

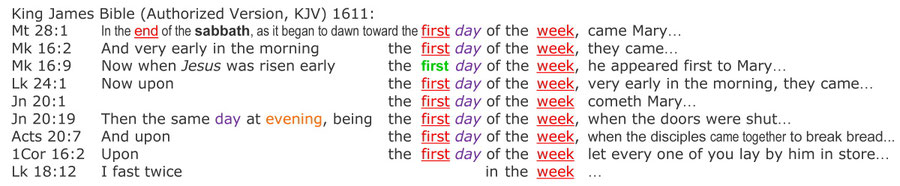

King James Bible 1611 - Authorized Version

The King of England, James I (King James, *1566, †1625) commissioned nearly 50 theologians and scholars to retranslate the Bible in accordance with Anglican Church doctrine to update spelling and statements. This was the third Bible translation produced by the Church of England after the Great Bible 1539 and the Bishops' Bible 1568. Since this "King James Version" (KJV) was officially approved and recommended by both state and church, it was given the name "Authorized Version" (AV). The first printing was done in 1611 in London by Robert Barker (see info and facsimiles). Many more editions followed, of which the one of 1769 is the most widely distributed. In concrete terms, this means that the official King James Bible was not published until almost 90 years after the NT by Martin Luther (1522). King James supported witch trials and personally supervised the torture of women accused of being witches. Several historical sources show that he was bisexual and liked the presence of beautiful young men. This is not only written in Wikipedia, but also in other sources. Some Christians question this because it damages the reputation of this Bible translation. Very few people who read the KJV today know this. King James was not at all interested in translating the statements of the Bible literally, but in publishing a Bible that would be accepted throughout his kingdom by both Catholics and Protestants. Therefore, various verses were translated by the many scholars not in the way God meant them, but in accordance with the church dogmas to avoid conflicts. This is an important fact to know the reason of the mistakes. The English king and his church were not interested in their subjects finding the unloved Jewish Resurrection Sabbath in the Bible. Therefore the Sabbath was simply replaced by "first day of the week" after stately and church censorship. The "day" in italics indicates that it is not a word found in the original Greek text of the NT. However, the addition of the word "week" and the removal of the word "Sabbath" in the singular and plural, has brought a quite different meaning to the NT. This Bible, which is popular in England and the USA, still bears the name of a worldly person who did not want to know anything about following Jesus Christ and eliminated the Resurrection Sabbath from the Bible. It is a joke when some pastors today claim that the KJV translation was allegedly "inspired by the Holy Spirit." Whoever compares the text with the basic Greek text will find several errors (see The KJV is not inspired by God). The blood of the women who were tortured as alleged witches says to this day, "how can you believe that this king was inspired by the Holy Spirit?"

In the course of time, the KJV became one of the most widely printed Bibles in the world. It was exported in large quantities to America, as printing outside England was forbidden. The first English language Bible was not printed in America until 1782 (Aitken Bible; NT 1777). It still contained the text of the KJV. So while English Catholics in France (Douay-Rheims Bible) and millions of Christians in Germany (Luther Bible) continued to find in their Bible the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning", the Anglican brothers and sisters in England and the USA had no opportunity at all to find out the true wording of the basic Greek text. Most pastors in the USA and in other parts of the world (Australia), therefore, had preached the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sunday" in a good intention, because it was just so in their Bible. The KJV played a significant role in officially putting the unloved Sabbath behind a curtain of secrecy so that the whole Christian world could uniformly celebrate the pagan Sun God Day (Sunday). Even Christian churches that kept the Sabbath preached the resurrection of Jesus at the end of the Sabbath and the appearance to the women "on a Sunday morning" (see Church Opinions). All this was only because the King James Bible was mistranslated in the decisive passages. The KJV contains many inaccuracies, it defines some important words (sheol, hades, hell, soul) incorrectly, so that the reader can never know in what condition and where the deceased are. The error in Acts 12:4 is dramatic and terrible, because here the biblical "Passover" is replaced by "Easter". This is very bad, seeing that Easter does not follow the biblical calendar of God, but the Catholic calendar. God loves and mentions the Sabbath seven times, but King James and his Church love and mention Sunday six times. Only in Mt 28:1 was the alleged end of the Sabbath mentioned. But this is impossible, because the end of the Sabbath is always at sunset. If it just becomes light on a day, then an event is exactly in the middle of a whole Sabbath day and not at its end. At the end of the Sabbath it does not become light, but dark. This shows that neither the king nor his church was interested in the calendar of God. That is why they did not know that Jesus rose from the dead "on the first Sabbath" (see the illustrations about the resurrection day of Jesus).

In 1631 the royal printers Robert Barker and Martin Lucas from London printed 1000 copies of the KJV, but with a dramatic printing error, for in Ex 20:14 it said "Thou shalt commit adultery". The error (the word "not" is missing) was discovered late and all Bibles were to be destroyed, but at least 10 copies have survived to this day (copy1, copy2, copy3). They are known as the Wicked Bible, Adulterous Bible or Sinners' Bible, and make high profits at auctions:

The KJV was revised several times. For example, "The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments, in the Common Version", translated by Noach Webster (*1758, †1843), appeared in 1833, which was also called Webster's Translation 1833. It still contains the Sabbath in Mt 28:1a, but in the other passages there are hardly any differences. After this, the Revised Standard Version 1946 (RSV) was published, which in turn was a revision of the already revised edition of 1881-1885 and the American Standard Version (ASV) of 1901. It does not contain any noteworthy innovations. The Third Millennium Bible 1998 is not a new translation, but only an update of the KJV of 1611, so the Sabbath is preserved in Mt 28:1a. The New King James Version Bible (NKJV), published in 1975 (Thomas Nelson Publishers), also improves the English language, but its content (except for Mt 28,1) hardly differs from the KJV 1611.

The King James Version 2000 (KJV2000) kept the Sabbath in Mt 28:1. Similarly translated are the King James Bible Pure Cambridge Edition and the King James Bible Clarified NT 1998.

The KJV with Strong Numbers

The American theologian James Strong (*1822, †1894) created an alphabetical list and concordance of all Hebrew and Greek words. Afterwards each biblical word was assigned a number. This number was then placed after the English words of the then most widespread KJV. In this way even laymen could quickly look up which of the over 5,500 Greek words was actually hidden behind an English word. So if somebody looks up the word "week" under the number 4521, he can clearly see that this is actually the word "Sabbaton", which occurs 68 times in the NT and is always translated as "Sabbath" (58 times in 53 verses: Mt 12:1,2,5,8,10,11,12; 24:20; 28:1; Mk 1:21,23,24,27,28; 3:2,4; 6:2; 16:1; Lk 4:16,31; 6:1,2,5,6,7,9; 13:10,14,15,16; 14:1,3,5; 23:54; 23:56; Jn 5:9,10,16,18; 7:22,23; 9:14,16; 19:31; Acts 13:14,27,42,44; 15:21; 16,13; 17:2; 18:4; Col 2:16), except in the few passages dealing with the day of Jesus' resurrection and the church assembly (Mt 28:1; Mk 16:2,9; Lk 18:12; 24:1; Jn 20:1,19; Acts 20:7; 1Cor 16:2). See the interlinear text. In the latter passages exactly the same word was twisted all at once for no reason as "week", just so that Jesus would have a Sunday resurrection. This is clearly wrong, as there has always been a separate Greek word for week (see definition), long before the English language even existed. It was mentioned in the Greek OT (LXX), but not in the NT. Likewise mia (a, one) was also reinterpreted in the KJV as first, but only in the resurrection chapter. It is interesting that in the KJV at Mt 28,1 the 100% identical Greek word "sabbaton" was translated once as "Sabbath" and the other as "week", which clearly shows the manipulation. So the Strong numbers are a very valuable help to uncover the translation errors of the KJV and other Bibles in a simple way.

Quaker Bible 1764

Anthony Purver (*1702,†1777) was of the opinion that the KJV contained numerous errors. But even his work, printed in London, shows hardly any improvements ("A New and Literal Translation of all the Books of the Old and New Testament"; see info and facsimiles). He did not differentiate between Greek prote (first) and mia (one) in the basic Greek text, which resulted in clear errors of understanding. Although in a footnote to Mt 28:1 he quite correctly stated that by evening (opse) he meant the entire period of the night until the morning light (see definition day), he nevertheless adds the word "after" to the Bible. So he completely distorts the statements of the evangelists. He points out very correctly that the Sabbath does not at all mean the week, but in Mk 16:9 he himself does not keep his own rule. In order to be able to justify the "Resurrection Sunday", he quotes a commentary according to which in Judaism all days of the week were supposedly mentioned as "first/second/third to the Sabbath" (or: after the Sabbath). However, this is not so, because otherwise no man could say "on a Sabbath" or "on the first Sabbath", because otherwise he would always have to mean "after the Sabbath". Jesus was "3 days and 3 nights" in the grave and not less. For this reason alone, the Good Friday and Easter Sunday tradition is unacceptable. In Mt 28:1 he omits the second Sabbath altogether, because otherwise he would produce an illogical double repetition "after the Sabbath", which expresses his helplessness.

Aitken Bible 1777, 1782

At the time when America was at war with England, it was difficult to get English language Bibles. All Bible printing outside of England was strictly forbidden. Because of the economic embargo no English Bibles could be imported, the Philadelphia-born printer Robert Aitken (*1734, †1802) decided to produce his own copies. The Aitken Bible 1782/83 (NT 1777) was the first English language Bible to be printed on the American continent. Aitken had previously received permission to publish it from the American Congress. However, it was not the first Bible to be produced in America. 119 years ago, the Eliot Indian Bible 1663 (NT 1661) was already produced in the language of the Indians (Algonquin), but it was translated from the faulty Geneva Bible and thus included the "Resurrection Sunday". In 1709, about 70 years before the Aitken Bible, the first Bible book printed on the American continent appeared in English. It was the two-column Algonquin Bible printed in Boston in 1709 with the English (Geneva-Bible) and the Indian text by John Eliot (*1604, †1690; the "Apostle of the Indians") next to it, but which only contained the Psalms and the Gospel of John. But the Aitken Bible was not the first complete American Bible to be produced in a European language. For 40 years before the Aitken Bible, the German Saur Bible was produced in America in 1743 (see facsimiles). It contained the translation by Martin Luther, with which the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" (and not "on a Sunday") was first proclaimed to the American continent. The special feature of the Aitken Bible was its handy format, which meant that soldiers could always carry it with them. It was therefore given the name "The Bible of the Revolution". But since this edition contained the text of the faulty King James Bible 1611, the true resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning" was hidden from the soldiers.

Numerous Bibles in many languages teach the resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath morning:

7. Many old Bibles proclaim the resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath or Saturday morning

7.1 Greek Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.2 Latin Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.3 Gothic Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.1 German Bible manuscripts show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.2 German Bible prints 1 (before Luther) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.3 German Bible prints 2 (since Luther) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.4 German Bible prints 3 (since 1600 to 1899) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.5 German Bible prints 4 (since 1900) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.1 English Bible manuscripts show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.2 English Bible prints 1 (from 1526 to 1799) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.3 English Bible prints 2 (from 1800 to 1945) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.4 English Bible prints 3 (from 1946 to 2002) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.5 English Bible prints 4 (since 2003) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.6 Spanish Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.7 French Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.8 Swedish Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.9 Czech Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.10 Italian Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.11 Dutch Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.12 Slovenian Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

"Prove all things; hold fast that which is good. Abstain from all appearance of evil"

(1Thess 5:21-22)

"Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them"

(Epheser 5:11)