- Home

- English

- Structure of the Bible

- Structure of the Menorah

- Ancient Menorahs

- Calendar and Feasts

- Resurrection on Sabbath

- Introduction

- Day

- Sabbath

- High Sabbath

- Pre-Sabbath

- Week

- Interlinear Bible

- Church Opinions

- 1. No Sunday

- 2. A Sabbath

- 3. No Friday

- 4. Intermediate Day

- 5. Three Days and Three Nights

- 6. Manipulations

- 6.1 Sabbath not Sunday

- 6.2 Plural σαββατων not week

- 6.3 one not first

- 6.5 Day of the Sabbaths

- 6.7 Lords Day

- 7. Old Bibles

- Greek Bibles

- Latin Bibles

- Gothic Bible

- English Manuscripts

- English Bible Prints 1

- English Bible Prints 2

- English Bible Prints 3

- English Bible Prints 4

- German Manuscripts

- German Bible Prints 1

- German Bible Prints 2

- Spanish Bibles

- Italian Bibles

- Swedish Bibles

- Czech Bibles

- μια των σαββατων

- Mt 28-1

- Mk 16-2

- Mk 16-9

- Lk 24-1

- John 20-1

- John 20-19

- Acts 20-7

- 1Cor 16-2

- Lk 18-12

- 7 Languages

- Palm Sabbath

- Omer

- Summary

- The Rapture

- Rabbi Kaduri Note

- 666

- 888

- Video

- Info

- Historic Bibles Facsimiles

- Francais

- Deutsch

- Espanol

- Dutch

- Ελληνική

- Pусский

- Introduction

- Day

- Sabbath

- High Sabbath

- Pre-Sabbath

- Week

- Interlinear Bible

- Church Opinions

- 1. No Sunday

- 2. A Sabbath

- 3. No Friday

- 4. Intermediate Day

- 5. Three Days and Three Nights

- 6. Manipulations

- 6.1 Sabbath not Sunday

- 6.2 Plural σαββατων not week

- 6.3 one not first

- 6.5 Day of the Sabbaths

- 6.7 Lords Day

- 7. Old Bibles

- Greek Bibles

- Latin Bibles

- Gothic Bible

- English Manuscripts

- English Bible Prints 1

- English Bible Prints 2

- English Bible Prints 3

- English Bible Prints 4

- German Manuscripts

- German Bible Prints 1

- German Bible Prints 2

- Spanish Bibles

- Italian Bibles

- Swedish Bibles

- Czech Bibles

- μια των σαββατων

- Mt 28-1

- Mk 16-2

- Mk 16-9

- Lk 24-1

- John 20-1

- John 20-19

- Acts 20-7

- 1Cor 16-2

- Lk 18-12

- 7 Languages

- Palm Sabbath

- Omer

- Summary

German Bible prints since Luther until 1599 and "Sabbath"

As has already been shown (facsimiles see German Bibles and Luther Bible), Martin Luther was not the first to translate the Bible into German. There were over 150 German Bible translations before his time and 18 different German Bible translations were printed even decades before the Luther Bible. They all always proclaimed the resurrection of Jesus with very clear words "on a Sabbath" or "on a Saturday" morning (see German Manuscripts and pre-Lutheran Bibles).

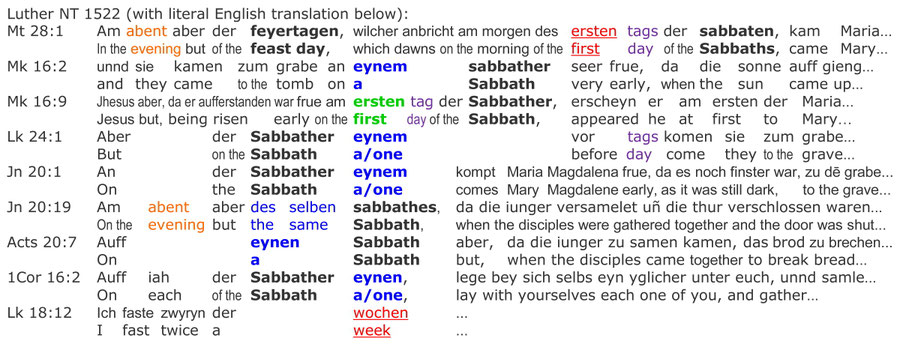

Luther NT 1522

Luther correctly translated the resurrection chapters of the NT. He speaks of a resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" morning or "on the first Sabbath". This is the statement of the Greek basic text and also of the Latin Vulgate. Both do not contradict each other. However, he was not at all concerned with the Sabbath question as such, but rather with correctly translating the biblical word into German. His guiding principles were: "sola scriptura" (Latin for "only Scripture") and "the word they shall leave standing!" ("das Wort sie sollen lassen stehn!"). Almost all readers of the revised 1984 Luther Bible, which is widely distributed in the German-speaking world today, are not even aware that Luther did NOT speak of the Resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ on Sunday, but rather of the Resurrection on the Sabbath! This was not a new message, for the many German manuscripts and the first printed German Bibles all speak of Jesus' resurrection "on a Saturday morning". Today's Luther Bible of 1984 does NOT correspond to Luther's statements in some passages, but rather to those of the theologians who were born about 400 years after him. This is a fact that can easily be proved. Until around the year 1900 it was not even possible to find a Luther Bible that spoke of the resurrection of Jesus "on the first day of the week", because all Luther Bibles printed millions of times and worldwide always spoke only of the Sabbath (see many Facsimiles). The German-speaking world was a light in this world for many centuries, for nowhere else was the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" proclaimed so clearly and so widely in the Bibles. Even if the churches taught Sunday orally, the Catholic and Protestant Bibles have always written about the Resurrection Sabbath or Saturday. The following text shows the original Luther text from 1522, the first edition of the NT (September Testament) printed in Wittenberg. The December Testament and the works printed in 1522/23/24/25 in Basel and Zurich also contained the same content. "On a Sabbath" (Auff eynen Sabbath) and "on the Sabbath one" (an der Sabbather eynem) mean exactly the same in old German, namely "on a Sabbath", but neither "Sunday" nor "week". Mk 16:9 menas: "early on the first day of the Sabbath" (frue am ersten Tag der sabbather). And John 20:19 means: "But on the evening of the same Sabbath" (Am abent aber des selben sabbathes). Every little German child understands that. Jesus did not appear to the disciples "on the first day of the week", nor "on the same Sunday", but "on the evening of the same Sabbath".

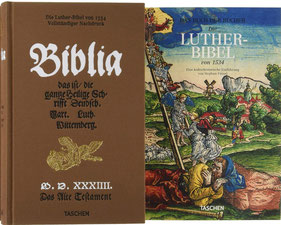

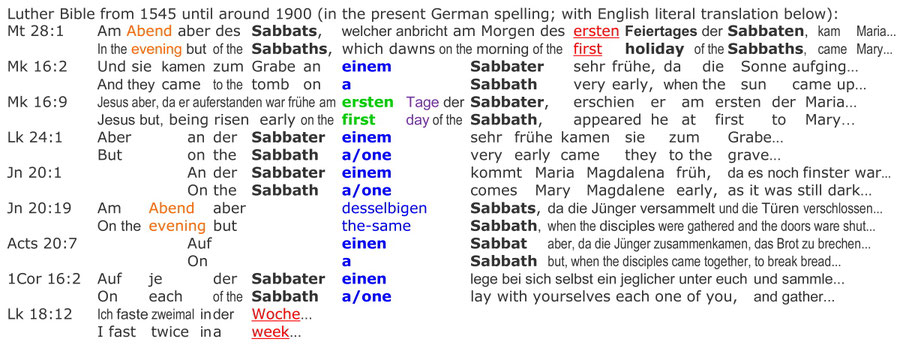

The Luther Bibles, which were reprinted for about 400 years (until their revision) only differed in spelling, but not in content. They reported about this long period of time about the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" (old German "an der Sabbather eynem"; modern German: "an einem Sabbat") and the assembly of the church "on a Sabbath" (eynen Sabbath; Acts 20:7). Again, when did Jesus appear to the disciples? It was "on the evening of the same Sabbath" and not "on the same Sunday". A revision of Luther's statements did not take place until around 1900. The official revised Bibles with falsified Luther texts appeared in 1912 and 1984. But until today, the original Luther Bibles from 1534 (first complete Bible, OT and NT) and from 1545 (Luther's "last hand" editing; facsimile edition in Fraktur script) are reprinted. These Bibles can be bought for little money, so every Christian has the Resurrection Sabbath in his house. Based on the precious original Luther Bible of 1534, now a UNESCO World Document Heritage Site, the volume from the Duchess Anna Amalia Library (Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, see Facsimiles) reveals the multi-faceted splendour of this Bible, with its accurate typeface, ornate initials and exquisite coloured woodcuts from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder. This means that for more than 500 years the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" morning has been proclaimed in German-speaking countries:

The facsimile edition of the Merian Copper Bible from 1630 (Merian Kupferbibel), produced only a few years ago, is also spectacular. Matthäus Merian (*1593, †1650) was one of the world's best engravers of all times. The Bible contains the original text by Martin Luther. The New Testament tells of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" morning and the appearance of Jesus before the disciples "on the evening of the same Sabbath" (Source: Ziereis Facsimiles OT-1, OT-2, NT):

Martin Luther did not understand his own translation

Although Martin Luther correctly translated the Resurrection chapters in the Gospels, he did not understand the meaning and importance of his statements. His Bible speaks of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath". This is completely correct. The Catholic Church, on the other hand, orally taught the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sunday". The state and church Sunday holiday had been firmly established for many centuries. The Sabbath, on the other hand, was considered a day only for the Jews, from which a "good Christian" had to distance himself. When Luther translated the Bible, he had to struggle with 4 major contradictions which he could not explain:

1. Martin Luther was NOT aware of the fact that the expression "on a Sabbath" and "on the first Sabbath" really meant the Sabbath day. This did not fit at all to the common church doctrine and most Christians of his time did not want to have anything to do with the Sabbath, because the churches had always kept Sunday holy and they did not want to have the same holidays as the Jews. In Mt 28:1 Luther oriented himself to the text of the Vulgate and wrote in the 1545 edition: "But on the evening of the Sabbath, which draws on the morning of the first holiday of the Sabbath, came Mary". This sentence is illogical and the word "holiday" has been added to the Bible. God never wanted to confuse us, His statements in the basic text are clear, which speaks of "on a Sabbath" day (see Interlinear Bible). Only the translations are confusing, because people have different opinions than God. Luther wanted to separate himself from the Jews and their feasts and tried to follow Catholic teaching and interpret this as if the first day after the feast Sabbath could be interpreted as the "first Sabbath". He wrote the following marginal note in his September Testament to Mt 28,1:

"("In the evening") Scripture begins the day the previous evening, and the end of the same evening is the morning after. Thus says here Saint Matthew: Christ rose in the morning; was resurrected at the end of the evening, and the first holiday was at the dawn, for they counted the six days after the high feast of Easter all holy, and began the first day, and the next day after the high feast of Easter."

[Original (in today's spelling): "("Am Abend") Die Schrift fängt den Tag am vergangenen Abend an, und desselben Abends-Ende ist der Morgen danach. Also spricht hier Sanct Matthäus: Christus sei am Morgen auferstanden; an des Abends Ende und (als) Anbruch des ersten Feiertages war; denn sie zählten die 6 Tage nach dem hohen Osterfest alle heilig; und fingen den ersten (Tag) an, dem nächsten nach dem hohen Osterfest"].

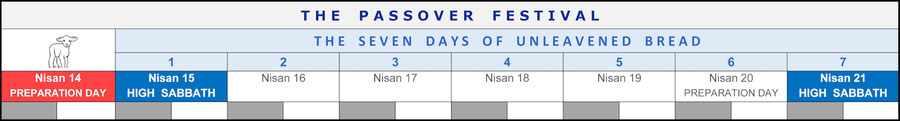

Here Luther describes very correctly that the whole night was considered "evening" by the Hebrews, since they did not divide the night into two calendar days (see definition). Thus the morning began at sunrise. In contrast to this, a calendar day of the Romans always began and ended at midnight (24 o'clock); therefore the Roman evening was already over at 24 o'clock and after that in the dark phase (the 6th hour) the morning began (see evening). A Roman calendar day has therefore not only parts of one, but of two night phases (see figure below). But according to Hebrew time, Jesus rose from the dead at the end of the evening (Hebrew: erev), i.e. shortly before it became light. All evangelists report this, because the women went to the tomb while it was still dark. Luther makes a mistake in his thinking, because according to the Catholic calendar he calls the feast "Easter" (instead of Passover), thus supplanting the biblical calendar with its corresponding days at Passover. He correctly translated and saw that the Bible speaks of the Sabbath, but he wanted to see the Sunday in the Bible. So he put forward the theory that the day after the High Sabbath (Nisan 15) was supposedly the "first holiday" (i.e. the "first Sabbath"). In his opinion, the Jews should consider all six days after the 15th Nisan as holy holidays (= seven Sabbaths). This is completely wrong, as any Jew can confirm. The holy days (high Sabbaths) were only the 15th and 21st Nisan. All other days (with the exception of the weekly Sabbath in between) were ordinary working days on which work had to be done and the early harvest brought in. To support his theory, Luther added the word "holidays" to the Bible, but it is not found in the basic Greek text nor in the Vulgate. Luther writes the following words in an interpretation of Mt 28:1 and Mk 16:1 dating from 1531:

“But when the high Sabbath, on which Christ lay in the tomb, had passed away [literally: "when yesterday was the high Sabbath"]. After that the Jews had seven whole days to celebrate, which they also called Sabbaths, and began to count the next holiday after the high Sabbath, and the same was called prima Sabbathorum, the third holiday after that they called secundum Sabbathorum, and so on."

[Original: “Aber als vergangen war der hohe Sabbat [wörtlich: “als gestern ist der hohe Sabbat gewesen“], an dem Christus im Grabe lag. Danach hatten die Juden 7 ganze Tage, die man feiern musste; die nannten sie auch Sabbate, und haben am nächsten Feiertag nach dem hohen Sabbat angefangen zu zählen, und der selbige wurde genannt prima Sabbathorum, den dritten Feiertag danach nannten sie secundum Sabbathorum und so weiter“ [slightly changed in today's German; Source: Luther: "Auslegung der Evangelien von Ostern bis aufs Advent" (Interpretation of the Gospels from Easter to Advent), Magdeburg, 1531; S. 23].

Since Luther followed the church tradition and wished for the Friday crucifixion and Sunday resurrection of Jesus, he called all seven days of the Passover week "Sabbaths" and "holidays" and the first day after the High Sabbath (15th Nisan), i.e. the 16th Nisan, he called "the first Sabbath" (first holiday), from which the 7 days of the feast were started to count, so that together with the High Sabbath there would be a total of 8 Sabbaths within a week. This statement is completely wrong, because the feast of unleavened bread lasts only 7 (not 8) days in total. It is counted from the 15th to the 21st Nisan (and not 22nd Nisan). The first (15th) and last day (21st Nisan) of the Passover Feast were High Sabbaths, all days in between were not Sabbaths but working days. Therefore, the 16th Nisan could never mean the "first Sabbath", neither then nor now, as every Jewish calendar proves. Moreover, the 16th Nisan is not the first day of the Passover (not the "first Sabbath"), but the "second day". And Jesus rose from the dead "on the third day" of Passover, but not "on the second day":

In the above illustration, the weekly Sabbath is still missing, which from year to year was either at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of the Passover week, unless the High Sabbath (15th Nisan) fell on the weekly Sabbath (a double Sabbath). In colloquial language, the 14th Nisan was sometimes called the "first day of unleavened bread" (Matthew 26:17), since all leaven had to be removed from it by sunset at the latest, but that was never a Sabbath, of course. After the first festival-Sabbath (15th Nisan) not 7 days but only 6 days are counted until the 21st Nisan, because the festival of unleavened bread lasts only 7 days. But what is even more important: it is about counting the 7 weekly Sabbaths until Pentecost. And this counting begins after the 15th Nisan (the first High Sabbath of the year; see counting of the Omer). So the first weekly Sabbath after the 15th Nisan is always the “first Sabbath“ of the “seven Sabbaths“ until Pentecost. Then the "second Sabbath" followed, then the "third Sabbath", and so on. This is a big difference. The 14th Nisan very often (statistically, about every third year, see Omer) falls on a Wednesday in the Jewish calendar, then the “first Sabbath“ falls on the 17th Nisan:

On Passover every year there are not 8 Sabbaths but only 3 Sabbaths, namely the two High Sabbaths or "Feast Sabbaths" (15th and 21st Nisan) with the weekly Sabbath in between. The High Feast Sabbath was always the "first day" of unleavened bread and the first High Sabbath (holiday) of the year. Therefore, the day after that cannot possibly be called the "first Sabbath" because it was the SECOND day of unleavened bread. What is even more important: It is completely impossible to call all seven days of unleavened bread "Sabbaths", since the days between the Sabbaths were normal working days on which work had to be done. They were working days to carry out the heavy harvest work. The only difference was that on them bread without leaven had to be eaten. That is why the festival is called "Days of Unleavened Bread". The Jews NEVER called these seven days "Sabbaths", because Sabbaths are days of rest or holidays and not working days. If a person eats unleavened crispbread on any day, he cannot claim that that day is a holy day of rest or Sabbath. Luther wanted to distance himself strictly from the Jews, so he looked for arguments to defend Sunday, although his translation was correct. The lack of knowledge of the Jewish calendar and Jewish customs meant that Martin Luther did not understand that the expression "first Sabbath" (mentioned only in Mark 16:9) meant nothing other than the first of the seven weekly Sabbaths between Passover (Nisan 15) until Pentecost (the 50th day; see counting of the Omer). But this was never the first working day after the Sabbath. In all other passages (except Mt 28:1) Luther translated correctly and spoke of the coming of the women to the tomb "on a Sabbath" [not the first Sabbath]. Every child understands this.

Jesus died on the 14th of Nisan at the same time that the lambs were slaughtered, "between the two evenings" (explanation), that is, at 3:00 p.m. After that there were 3 hours to bury Him before the 15th Nisan, the High Feast Sabbath, began. Jesus then rose from the dead exactly after "3 days and 3 nights" on the 17th Nisan, as he said himself. This was the sign of the Messiah, the most important sign in the history of the universe (more Info).

2. Luther overlooked the fact that the High Sabbaths (and thus also their preparation days) of the Passover can fall on any day of the week and have nothing to do with Saturday. A double Sabbath is also not possible, because otherwise Jesus would not be "3 days and 3 nights" in the tomb, and because there must be at least one day of the week between the High Sabbath and the weekly Sabbath (see intermediate day). Since Luther had equated the preparation day (14th Nisan) with Friday and the annual Sabbath (15th Nisan) with Saturday, he followed the common false Catholic opinion that Jesus must have died on a Friday (preparation day) before the High Sabbath (Saturday, double Sabbath) and must have risen on an Easter Sunday. If Luther had taken his own translation literally and studied God's calendar, he would have known that Jesus must really have risen on a Saturday morning and that He fulfilled the sign of the Messiah, the most important sign in the history of the universe; the sign which many Christians deny because they wish for the pagan resurrection Sunday.

3. Since Mk 16:1 clearly speaks of the preparation of ointments by women "AFTER the Sabbath", Luther assumed that this must have taken place on Saturday night (after sunset) or on Sunday morning. The day after the Sabbath is for him the Saturday night, which begins at sunset and includes the Sunday until the next sunset. This is wrong, for the NT distinguishes between the festive (High) Sabbaths and the weekly (ordinary) Sabbaths and does not lump them together. In reality, it was not just one Sabbath, but three Sabbaths in just one Passover feast week. The women prepared the ointments "after the [High] Sabbath" (Mk 16:1) and came to the tomb on the immediately following "on a [weekly] Sabbath" (Lk 23:55-56; Mk 16:2; Lk 24:1; Jn 20:1). Luther translated these passages correctly, but misinterpreted them according the the church doctrin. If God had meant Sunday, He would have said it (see No Sunday) and not spoken of the Sabbath 7 times (Matthew 28:1a,1b; Mark 16:2,9; Luke 24:1; John 20:1,19). Especially in John 20:19 Luther speaks of the "evening of the same Sabbath" and not "in the evening of the same Sunday". Every child understands the statements of the Luther Bible. It only becomes complicated when interpretations are to twist the Word of God. The Bible speaks 7 times of the Sabbath (in singular and plural) but the theologians speak 6 times (except in Mt 28:1a) of Sunday, a word which God did not write down once in the whole Bible.

4. According to Luther's thinking, Friday, Saturday and Sunday could be counted as "3 days", but this would be, as he himself writes, contrary to the opinion in Judaism. He confirms that according to Jewish counting, the period from Friday evening to Sunday morning can only mean 1.5 days and never three Jewish days. Luther could not understand why Jesus even spoke of "3 days and 3 nights" and how this could be classified, because in Judaism this means that in fact three days/nights at least begun on which Jesus was in the grave must be meant. Quote:

"Now the one question is, how do we say that He [Jesus] rose from the dead on the third day, and yet lay in the grave only one day and two nights? In Jewish terms, it is only a day and a half. But how can we now insist on believing that he was risen on the third day?"

[Original: “Nun ist die eine Frage, wie wir sagen, er sei auferstanden am dritten Tage, und hat doch nur einen Tag und zwei Nächte im Grab gelegen? Auf jüdisch zu rechnen ist es allein ein Tag und ein halber. Wie wollen wir aber nun bestehen, das wir drei Tage glauben?“ [Source: Luther, Martin: "Auslegung der Evangelien von Ostern bis aufs Advent" (Interpretation of the Gospels from Easter to Advent), Magdeburg, 1531; page 23].

If Luther had looked not at the Catholic (Gregorian, papal) but at the biblical calendar (the calendar of God), all confusion would have disappeared in a few minutes. That is why it is still very important today that Christians are familiar with the Old Testament. Anyone who despises the Old Testament will never be able to understand the New Testament either. The solution is so simple:

The sequence of days shown in the figure above is very frequent and statistically occurs in the Jewish calendar about every third year. This was also the case in the year 2020, which means that all those who are reading this text have often experienced in their lives the same sequence of days at the Passover as in the year in which Jesus was crucified. Yet even today most Christians do not have this knowledge, not only Luther. That is why they cannot criticize Luther, they are no better.

In order to avoid misunderstandings, it is not a question here of making Martin Luther bad. His courage and his translation cannot be praised highly enough, because although he did not understand the meaning (because he did not know the full extent of the calendar of God), he nevertheless translated correctly. And that is the most important thing. His statements are consistent with the many German Bible manuscripts that speak of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Saturday morning". Modern theologians, on the other hand, go the other way. They also do not know the biblical holiday order on Passover, but they translate incorrectly and write what they would like to have without referring at least 7 times in a footnote to the literal statements of the evangelists. God will judge these theologians and pastors of many churches accordingly, as they distort the Word of God and thus lead the children of God from the Sabbath to Sunday. God promised that knowledge will increase in the Last Days (Dan 12:4) and it is now time to point out these major translation errors in modern Bibles, and to refer to our origins, that is to say to the basic Greek text, futher to the Catholic Vulgate, the many good Catholic translations and the original Luther Bible.

Worms Luther Bible 1529

This edition printed in Worms by Peter Schöffers (Schöfern) (Title: "Bjblia bijder Allt and Newen Testaments Teutsch. Marthini Lutheri"; Facsimiles) was a so-called "combined Bible" from the Luther translation as well as the prophets and the Apocrypha from the Zurich Bible. The illustrations were by Anton Woensam. The first combined Bible was published in 1524 in Nuremberg (F. Peypus), as the OT of Luther was not yet available. Although the title page of the 1529 Bible contains the name of Luther, the text is identical to the Froschauer Bible (Zurich Bible of 1531; see below) except for minor differences in spelling. In Lk 24:1 and Joh 20:1 "one" was replaced by the word "first". This is not problematic, however, since this Sabbath mentioned is actually the first weekly Sabbath of the seven Sabbaths until Pentecost. Much more important, however, is the fact that the addition of the word "after" (nach) in Lk 24:1 gives rise to a translation error, for a sentence has been created which differs completely from all the other editions of Luther in terms of sentence structure and content. In the other verses this Bible speaks of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" and Jesus appeared to the disciples "on the evening of the same Sabbath":

Luther NT 1531 and 1534

Since 1522 several printed editions of the Luther Bible have been published (Facsimiles), in which the text has been somewhat improved. So were the copies produced in 1531, 1535 and 1538 in Nuremberg by the publishers Jobst and Jodocus Gutknecht with the inscription "Das new Testament Teutsch" (The New Testament German). This text was also the content of the first complete Luther Bible (OT and NT), which was printed in Wittenberg in 1534. Particularly noticeable is the improvement in Mt 28:1a, which shows that it was clearly the "on the evening of the Sabbath holiday" (am abent aber des sabbaths feyertages; and not the Sunday) on which the women went to the tomb. Also the other passages clearly speak of a coming of the women to the tomb "on a Sabbath" (an einem Sabbath), but never "on a Sunday" (an einem Sonntag) nor "on the first day of the week" (am ersten Tag der Woche):

Luther Bible from 1545 until around 1900

The last edition published during Luther's lifetime was that of 1545, hence the term "last hand edition" ("Ausgabe letzter Hand"). Some modern Bible programs do indeed mention the year 1545, but in the chapter on resurrection of all places they did not take over Luther's original text, but the text revised 400 years later, which replaces "on a Sabbath" with "on the first day of the week". This is clearly wrong and unacceptable, as many original facsimiles prove. If Luther had not meant the Sabbath but the week, he would have written it. He himself used the word "week" in many places in the Old Testament (Gen 29:27f; Ex 34:22; Lev 12:5; Num 28:26; Dt 16:9,10,16; Book of Daniel) and even in the New Testament in Lk 18:12. However, most websites and programs publish the correct text of the original Luther Bible of 1545, but in today's German spelling. And this text of course speaks of a Sabbath morning.

In the year 1630 the famous Merian Copper Bible (Merian Kupferbibel) was produced in Strasbourg (Germany at that time, today France). Today it is of inestimable value and has been available as a facsimile reprint since 1984 (see pictures and link above). So every Christian can see that the precious letters announce the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" morning. The copper engravings are by Matthäus Merian (*1593, †1650), one of the world's best engravers of all times.

The Luther Bible of 1545 has been reprinted millions (!) of times by Bible Societies in many countries of the world in very many editions. Baron von Canstein (Freiherr von Canstein; *1667, †1719) founded the Canstein Bible Institute (Cansteinsche Bibelanstalt) in Halle in 1710 with his own starting capital. It was the first Bible Society (German: Bibelgesellschaft) in the world and the only one in the 18th century. The first English Bible Institute was not founded until 100 years later (1804 to be precise). The Cansteinsche Bibelanstalt made it its business to reprint the text of Luther in very large numbers, so that especially the poorer population from 1713 (NT) and 1717 (full Bible) could be offered a cheap Bible. Thus the gospel of the resurrection of Jesus Christ "on a Sabbath morning" was spread worldwide from Germany. By 1934, about 10 million Luther Bibles had been produced in Halle alone. From 1700 onwards, far more people were able to read in percentage terms than in Luther's time. Thus, poor and rich people from all social classes learned about the biblical resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath", even though the churches taught something different (Sunday) in their sermons. Canstein found many helpful celebrities, e.g. the Prussian Queen Sophie-Luise (*1685; †1735), the wife of the first Prussian King Frederick I (Friedrich I; *1657 in Königsberg; †1713 in Berlin), whose donations were used to finance the letters and printing presses. Thus it was not the churches but private individuals and the secular Prussian rulers who contributed to the widespread distribution of the Bible (= the Word of God). This is a fact which does not cast a good light on the large churches and thus one question finds its justification: "Why did you as a church not contribute to the spreading of the Bible in the national languages and instead persecuted and killed the translators?" The external construction of large and expensive church buildings was more important than the inexpensive spiritual construction of the church based on the biblical foundation.

The first Bible printed in a European language in the whole of America was not an English or Spanish Bible, but the German Saur Bible of 1743 (Facsimiles). Based on the Luther text of the 34th edition of the Canstein Bible of 1743, it proclaimed to the American continent from the beginning the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" morning. This is the message that not only Europe but also America heard first.

Even in the many printed editions from 1756 (Halle), 1812 (Lancaster), 1817 (Breslau in Silesia), 1818 (Leipzig), 1825 (Stuttgart), 1828 (Philadelphia, USA), 1831 (Berlin, London), 1834 (Sulzbach), 1841 (Philadelphia), 1847 (Leipzig), 1857 (St. Luis, USA), 1858 and 1866 (London), 1867 (Berlin, Frankfurt, Karlsruhe and Cologne), 1869 (Frankfurt), and in New York (1880, 1835, 1837, 1853, 1854, 1874, 1877, 1887, 1889, 1891, 1895, 1899...) the resurrection of Jesus was still everywhere in it "on a Sabbath" morning. Even after 1900 (e.g. 1903, 1905, 1906 and 1907 in New York) many Luther Bibles were reprinted which contained the same text with the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath". This was also the case in the Volks-Bilderbibel, printed in Leipzig in 1844, which was very popular in German countries and published the unchanged Luther text. Even in 1972 a reprint of Luther's original translation was produced in Munich. In concrete terms, this means that until the revision of the Luther Bible over 1,800 years, all these Latin (Vulgate) and German (Luther) Bibles clearly spoke of women coming to the tomb "on a Sabbath". This is not new information, but ancient basic knowledge from the first early Christian congregation (see original facsimiles). And until today (that means for more than 500 years) the original Luther Bibles from 1534 (first complete Bible), 1545 (Luther's last Hand Edition) and 1630 (Merian Copper Bible) are reprinted and can be bought for little money online or in bookshops:

The American Bible Society had several Luther Bibles printed around 1850 with a small peculiarity, because instead of "on a sabbath" or "on one of the Sabbaths" (as Luther wrote), now without reason "on the first Sabbath" ("an der Sabbater erstem": Lk 24:1; Jn 20:1; or “am ersten Sabbater“: Mk 16:2; Acts 20:7) was translated. Although this is not exact, it is still correct in terms of content, since this is actually the first of the seven Sabbaths up to Pentecost. Several bilingual editions were also published in New York (e.g. 1854, 1857, 1860), whereby the Luther Bible proclaimed the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath", while the English version spoke of the "first day of the week".

From 2012, the German Bible Society (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft; www.bibelonline.de) has published an inexpensive complete facsimile reprint of the first complete Luther Bible ("Volksbibel [People's Bible] of 1534" (Title: Die Lutherbibel - Vollständiger Nachdruck der ersten Bibelausgabe in der Übersetzung Martin Luthers 1534 [The Luther Bible - Complete reprint of the first edition of the Bible in the translation by Martin Luther in 1534]). The advertising text reads: "Normally, this Bible lies well locked in a display case of the Duchess Anna-Amalia Library [Herzogin-Anna-Amalia Bibliothek] in Weimar and only selected people are allowed to have a look at this special book". Already in 1987 the German Bible Society published the facsimile "Biblia Germanica" (Luther translation 1545 - last hand edition) and it is admitted: "In its version of 1545 the Luther Bible was in use in Germany until the 19th century". That is absolutely correct. But what does this mean in concrete terms? It means that in all these many editions over the centuries (until today) only the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" was reported. There was never any mention of an Easter Sunday fairy tale by the words "on the first day of the week" or "the day after the Sabbath" or "on a Sunday". These two recently reprinted Bibles of 1534 and 1545 can now be purchased by every Christian, and thus the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning" can be purchased officially and for little money.

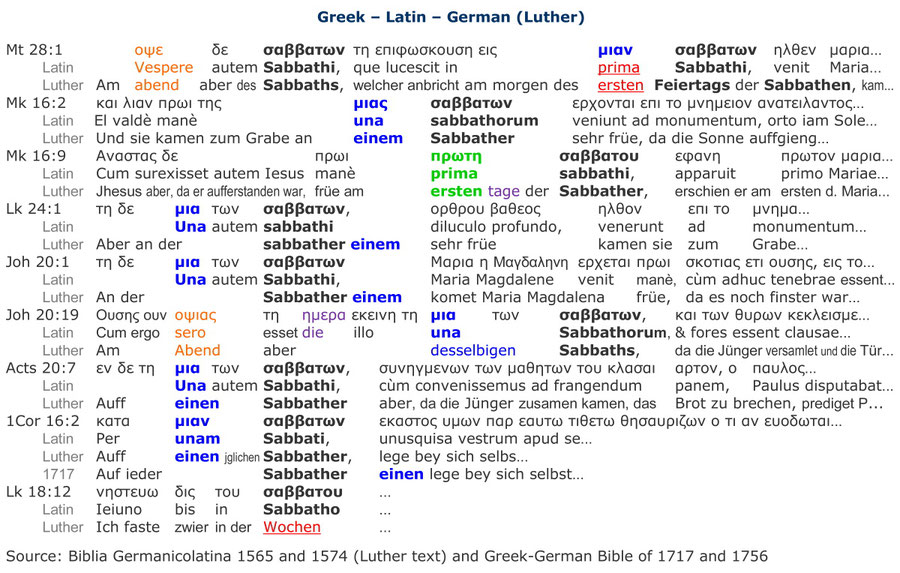

Luther Biblia Germanicolatina 1565-1574 and Greek-German Bible 1717-1756

Already in 1565 and 1574 a magnificent Latin-German version of Luther's translation was published in Wittenberg. In both languages Jesus rose from the dead "on a Sabbath morning". The Latin text differs slightly from the Vulgate in some verses, but this does not concern the time when the women came to the tomb. Greek-German editions were also published, e.g. 1717 in Chemnitz or 1756 in Halle (Gerhard von Mastricht: Hē Kainē Diathēkē, second edition). The comparison of these editions is very interesting, because in all languages you can read for centuries that Jesus rose from the dead "on a Sabbath" and not on the "first day of the week" and not "on a Sunday". In Mt 28:1b Luther has taken over the translation error of Jerome, who instead of speaking of "one" now spoke of the "first Sabbath". This error was also copied to Luther by many who did not have the basic Greek text. But this is not a problem, since this Sabbath was actually the first of the seven Sabbaths up to Pentecost. Every child understands this. If we now take the text of the Latin Vulgate as well, it becomes clear that all three languages and therefore all three Bibles do not differ in their content:

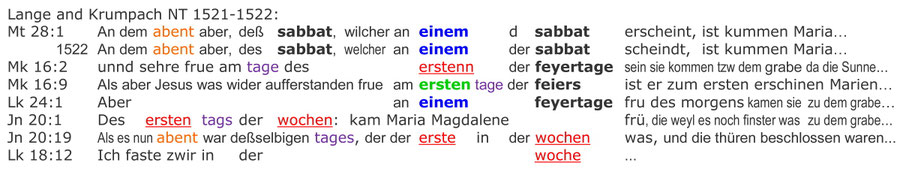

Lange and Krumpach NT 1521-1522

The Gospel of Matthew was translated from the Greek text of Erasmus into German by Johannes Lange (facsimiles). One edition was published as early as 1521 (i.e. before the September Testament of Luther) and the other in Leipzig in 1522, but translated from the Vulgate. The astonishing thing is that in Mt 28:1b there is talk of "a Sabbath" (not "first Sabbath"), as it is also written in the basic Greek text, while the Vulgate literally speaks of the "first Sabbath". Nevertheless, Lange has understood that both languages mean the same, namely "on one of the Sabbaths" ("an einem der Sabbat") and on no other day. Nicolaus Krumpach (facsimiles) translated Mark, Luke, John, Timothy, Peter. He calls the Sabbath in the gospel of Mark "a holiday" (so also Mk 16:1). But in John's gospel he speaks of the week for no reason, creating great contradictions himself. Martin Luther translated John 20:1,19 much better in the same year.

Zurich Bible = Froschauer Bible 1524, 1530/31

Also in the first Bibles printed in Zurich (Facsimiles) the resurrection of Jesus took place "on a Sabbath" and "on the first Sabbath day", meaning the first of the 7 Sabbath days until Pentecost. Especially John 20:19 makes it clear that it is about the "evening of the same Sabbath" (abent desselben Sabbaths). Thus it was clear to all readers from Switzerland that Jesus did not rise from the dead "on a Sunday", which meant that the Good Friday and Easter Sunday tradition could be declared biblically invalid. The New Testament appeared in the Froschauer printing house from 1524 and the first Protestant full Bible was published in 1531. Its contents spoke of the Sabbath and of no other day before or after it. There is an error in Lk 24:1; because here the word "after" was added to the Bible, which is neither in the Greek basic text nor in the Latin translation (Vulgate):

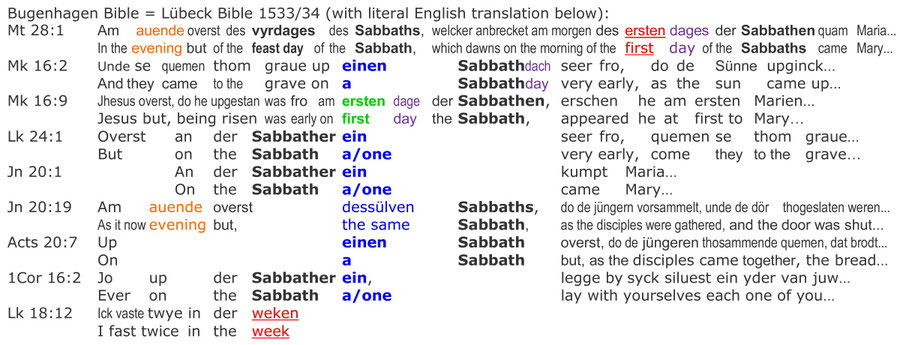

Bugenhagen Bible = Lübeck Bible 1533/34

The reformer Dr. Johannes Bugenhagen (*1485, †1558) was wedding pastor and close friend of Martin Luther. He had the Luther Bible translated into Low German and had it printed by Ludwig Dietz in Lübeck (=Lübecker Bible of 1533/34; not to be confused with the pre-Lutheran Lübecker Bible of 1494, Link). Title: "De Biblie: vth der vthlegginge Doctoris Martini Luthers yn dyth düdesche vlitich vthgesettet mit sundergen vnderrichtingen alse men seen mach". This was also the first translation of the Luther Bible into another language ever. The NT, however, appeared in Wittenberg as early as 1524. Dietz was called to Copenhagen in 1548 by King Christian III to produce the first Danish Bible. His Lübeck colleague Jürgen Richolff had already been producing the first Swedish Bible (Gustav Vasa Bible; Link) in Sweden from 1539 onwards, based on the Lübeck Bible. In 1885 Johannes Paulsen produced the last printed edition of the Bugenhagen or Lübecker Bible (the so-called Paulsen Bible 1885, see below). Bugenhagen also clearly mentions the one Resurrection Sabbath and the assembly of the church "on a Sabbath" (English literal translation below):

The 3 Catholic Correction Bibles to the Luther Bible

Since Martin Luther was excommunicated by the Pope, it was to be prevented that the Luther Bible, now widely distributed since 1522, would also be read by German Catholics. It was too late for the destruction of the Luther Bible, as too many copies were already in circulation and several sovereigns protected the printing works. The Catholic Church had no other choice and had to provide its own translation. It was very eager to do so, because there was not only one, but three German counter or correction Bibles. They all used the Latin Vulgate as a basis. They were those of Hieronymus Emser (1527, only NT), Johann Dietenberger (1534) and Johannes Eck (1537). They were the official Catholic answer to Luther's Bible. Although they were called "Catholic Bibles", they hardly differed from Luther's text in their content, as they simply copied or transcribed some passages from his text. There is only a regional adaptation and use of certain words in Low and Upper German. It was not so much a matter of changing the content of the text itself, but rather WHO did the translation, i.e. how the translator stood by the teachings of the Catholic Church. So it is not surprising that also in these Catholic Bibles the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning" was a matter of course, was not questioned at all, and was still spread throughout the German-speaking world for a long time. It is true that the Catholic Church has officially preached the alleged Sunday Resurrection of Jesus to the people, but in all their own Latin and German Bibles there has been talk only of the Resurrection "on a Sabbath" for about 1,500 years now. Luther called the Pope the Antichrist and the Pope in turn called Luther an Antichrist, but both agreed on the biblical resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" morning, as now shown in the Catholic Bibles:

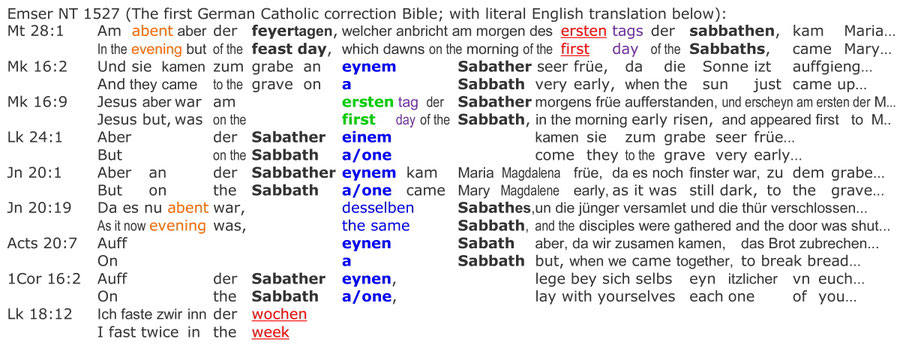

Emser-NT 1527 - The 1st Catholic Correction Bible

Hieronymus Emser had the same textual basis as Luther, namely the Catholic Vulgate of his church father and namesake Hieronymus (Jerome; *c. 347; †420) and a few basic Greek texts. It is therefore not surprising that Emser's German translation (see Facsimiles) always correctly mentions the Sabbath. For him the women came to the tomb "on a Sabbath" and "on the evening of the same Sabbath" Jesus appeared to the disciples. Also the church meeting of the first Christians did not take place "on a Sunday" in this Catholic Bible, but only "on a Sabbath". The Emsers edition, printed in Cologne in 1598, emphasizes on the title page that it was written in honor of the "lordly, highborn, highly noble Catholic prince W. Herzog Georgen of Saxony" and that it was "now newly corrected and improved". The spelling has been improved, but the content has remained exactly the same. In Mk 16:2 it says, "And they came to the tomb on a Sabbath very early..." This is a clear and definite statement that every German child understands. There is never any talk of a "first day of the week". Emser deliberately did not use the word Sunday, although he could have done so, for in the marginal note to Jn 20:19 he wrote that this should be read "Gospel on the first Sunday after Easter", which makes the difference between the biblical word and Catholic church doctrine clear. This Emser Bible has even been reprinted until 1713. It is an important example of the fact that even respected Catholics can translate the Bible text correctly and make a clear distinction between the words one/first and between Sabbath/Sunday/week, if they really want to. If someone were to reprint this Catholic Bible today, Catholics would be shocked and upset. The work of Emser cannot be valued highly enough. It is not about new teachings, but about the old original Catholic New Testament, according to which Jesus rose from the dead in writing "on a Sabbath", even if something else was taught orally. The facts are breathtaking:

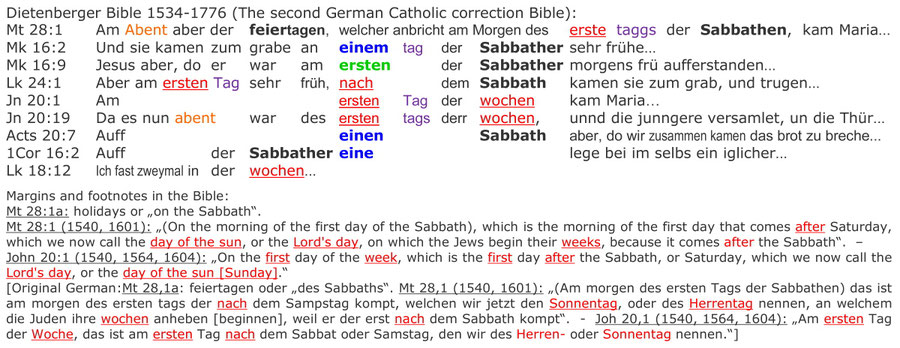

Dietenberger Bible 1534-1776 - The 2nd Catholic Correction Bible

Dietenberger (info and facsimiles) mentioned on the title page that his Bible was to serve the German nation. And exactly this Bible preaches the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning". The text in the 9 passages listed below has hardly changed from the first to the last edition. It does, however, contain contradictions, as in some passages it speaks of the resurrection Sabbath (Mt 28:1; Mk 16:2,9) and in other passages of the "first day of the week" (Lk 24:1; Jn 20:1.19), while the meeting of the church members (Acts 20:7; 1Cor 16:2) continued to take place "on a Sabbath". Dietenberger claims in a footnote that when the Jews said "on the first day of the Sabbath" they supposedly meant "the first day of the week", because it was the first day after the Sabbath. This is of course nonsense, for first of all the Jews never meant the first day of the week by this, and secondly the phrase "day of the Sabbaths" (plural) is mentioned in other passages in the New Testament, where it is always correctly translated as "on the Sabbath" (singular). Also the Septuagint knows this expression to describe a single Sabbath day. The Jews were quite capable of speaking from the first of the seven Sabbaths until Pentecost. But since Dietenberger despised the Jewish festivals and the calendar of God, he could not possibly know what the evangelists meant. However, in the gospel of Mark he translates correctly that the women came "on a Sabbath" and Jesus rose from the dead "on the first of the Sabbaths", namely on the first of the seven Sabbaths until Pentecost. It should be noted that in Acts 20:7 in the Greek basic text and in the Vulgate the same words are used as in Mark 16:2; Lk 24:1 and John 20:1, so it becomes clear that Dietenberger would have had to speak of "on a Sabbath" at all points if he had refrained from church interpretations. His footnotes and marginal notes create a chaos full of contradictions, because he distorts the meaning that he has correctly translated:

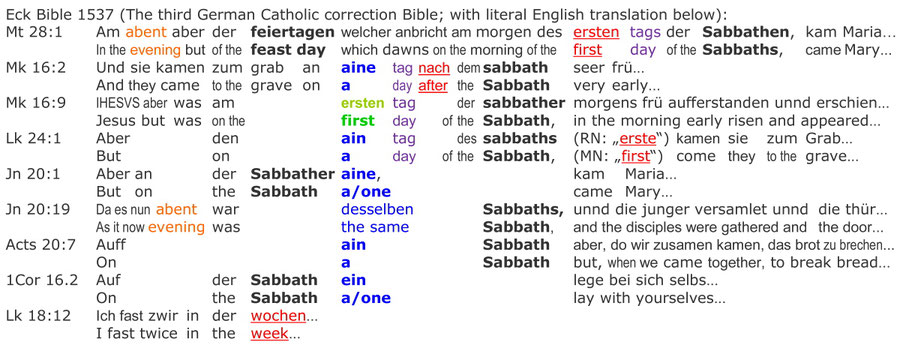

Eck Bible 1537 - The 3rd Catholic Correction Bible

Johannes [John] Eck wrote very hard books against the Reformers and against Luther. His translation (info and facsimiles) printed in Ingolstadt in 1537 was the third Catholic counter-bible. Its text version is reminiscent of the Emser Bible, because it corrected some of Dietenberger's mistakes. The Eck Bible was mainly read in southern Germany (Bavaria) and Austria until the 17th century. It was very popular there (7 editions). Until today many original Bibles are in several libraries and in all of them it is written when the women came to the tomb, namely: "on a day of the Sabbath" (Lk 24:1, not "on a day of Sunday") or "on the Sabbath one" (i.e. "on a Sabbath"; Jn 20:1). In Old German the word "one" was often set after the word "Sabbath", but always meant "on a Sabbath"; modern German grammar uses "one" always before the Sabbath. And "on the evening of the same Sabbath" (Jn 20:19) Jesus appeared to the disciples. Only in Mk 16:2 Eck spoke of "a day after the Sabbath", because verse 1 reports that the women prepared the ointments "when the Sabbath was over" and he did not know that there are always 3 Sabbaths in a week at Passover. It was not logical to him why women should come to the tomb after the Sabbath and "on a Sabbath", since a whole week cannot be in between. That is why it is so important to know the biblical calendar of God, then these questions disappear by themselves. The same text was used in the 1550 and 1558 edition printed in Ingolstadt (Weissenhorn publishing house). Even the edition published in Cologne in 1611 had the same content; only the spelling was improved. Although Eck as a Catholic kept the church Sunday holy, it was still clear to him that the resurrection of Jesus was biblically "on a Sabbath morning". On this point the Catholic Bibles and the Luther Bible were in agreement. Eck translated correctly and avoided speaking of a "first day of the week". Eck could not have formulated it more clearly. We love this Catholic Bible:

Conclusion on the 3 catholic correction Bibles

Anyone who says today that the resurrection of Jesus took place biblically "on a Sabbath" morning is not claiming anything new or even the opinion of a sect, but is proclaiming nothing more than an ancient official Catholic opinion, which high-ranking translators and theology professors authorized by the Pope have represented in the Bible for many centuries. The resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" was a written fact that was written in the Latin and German Catholic Bibles for over 1,800 years, although the alleged resurrection of Jesus was orally taught on Sunday.

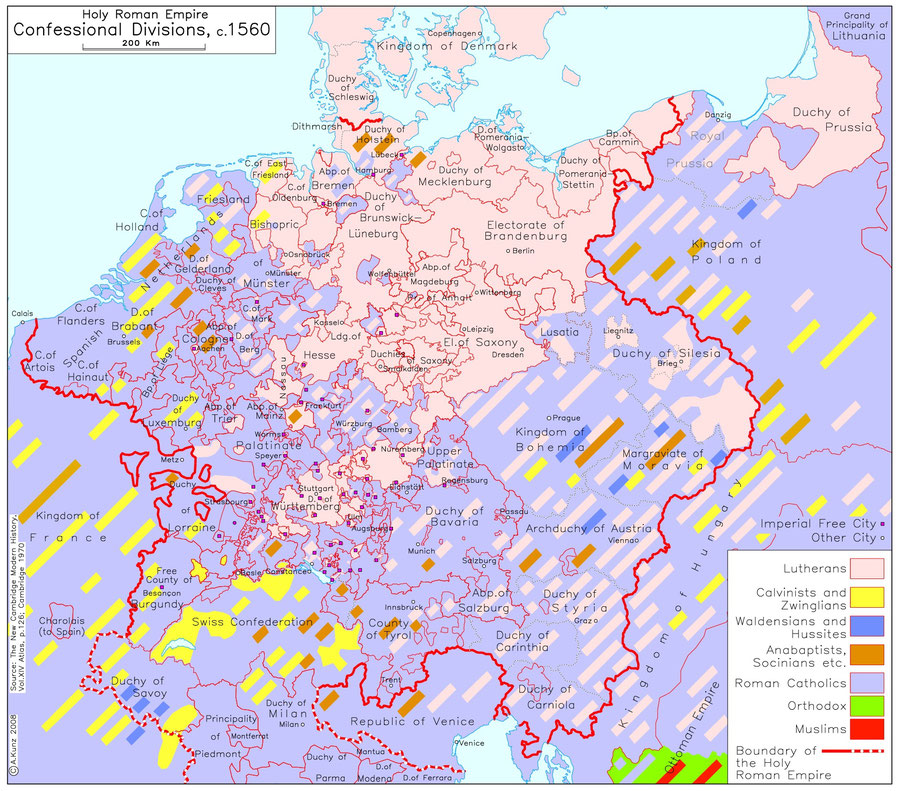

The Distribution of Confessions in Central Europe 1560

The map above (source) gives an idea of how difficult the life of the individual people was, because the religious differences were not only regional, but often also in the individual families.

More German Bibles until 1599

Martin Luther died in 1546, but even during his lifetime his Bible served as a basis for inspiration and translation for Bibles in other languages and for German editions for other denominations. As has already been shown, the first translators, who were all Catholics themselves, spoke of the Resurrection Saturday or the Resurrection Sabbath. The Protestants too were initially no different from the Catholics on this point. But whereas with Christians in the Protestant area the resurrection still took place "on a Sabbath" until the revision of the Luther Bible around 1900, in the sphere of influence of the Catholic Bibles this event was increasingly postponed to Sunday in some revisions or new translations already from the year 1600 onwards. However, there were not only Catholic, but also free-church and Lutheran or Protestant translators, such as Johann Albrecht Bengel (*1687, †1752) and Heinrich August Wilhelm Meyer (*1800, †1873; Bible of 1829), who in time also introduced the unbiblical "first day of the week". So it is not surprising that today Catholic and Protestant Bibles report uniformly of the alleged Sunday Resurrection. Most free-Lutheran pastors do not want to know anything about a Sabbath resurrection of Jesus until today, because they are aware that this leads to divisions within the church and can even cost them their own jobs. Some become aggressive at the word "Resurrection Sabbath". So they prefer to twist the words of Jesus (and ignore the sign of the messiah (Link) in order to continue celebrating their "beautiful Sunday service" and to lull themselves into a false sense of security. But God rewards those who are on His side and stand by His genuine Word. Today the Resurrection Sabbath is unknown to many Christians, although it was a biblical matter of course for the Catholic and Protestant churches for about 1,800 years.

Beringer Gospel Harmony (Beringer Evangelien-Harmonie) 1526

Jakob Beringer, vicar at Speyer Cathedral, published his complete NT in German in Strasbourg (then Germany, today France) in 1526 (Facsimiles). So this was even before the official Catholic counter-bibles of Emser, Dietenberger and Eck appeared. The special fact about it was that Beringer had combined the 4 Gospels into one Gospel harmony (Beringer Evangelien-Harmonie). In his text he also oriented himself to the translation by Martin Luther, but he did not copy it. Further editions appeared in 1529 and 1532. Under the heading "Easter Day", the then name for the Passover feast, we now learn when the resurrection of Jesus really took place, namely NOT "on the first day of the week" and not "on a Sunday" but "on a Sabbath". And Jesus of course appeared to the disciples "on the evening of the same Sabbath". Who does not understand this?

Gymnich NT 1537

The text is a Low German version of the Catholic Bible by Hieronymus Emser from 1527 (Info and Facsimiles). Gymnich clearly distinguishes between the Sunday (Sondag), which he often mentions in the preface, and the Sabbath, on which the women came to the tomb. His Catholic Bible translation is clear and unambiguous; both the resurrection of Jesus and the church meeting (Acts 20:7; 1Cor 16:2) took place "on a Sabbath". He could also distinguish in the basic Greek text between "one Sabbath" and "first Sabbath". Johann Gymnich could have spoken of the "week" if he wanted to, as Lk 18:12 proves, but he deliberately decided against it. Every German child understands this Bible and the words "on a Sabbath" and "on the same Sabbath" (Jn 20:19):

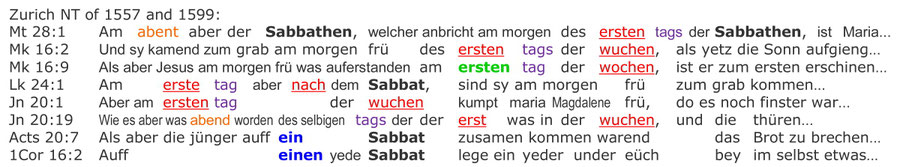

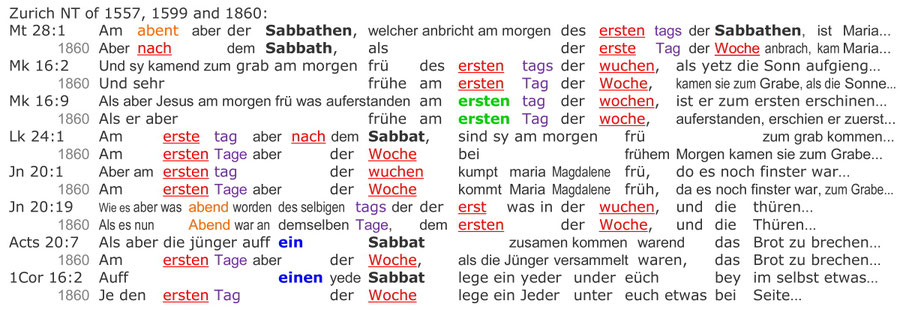

Zurich NT of 1557, 1599 and 1860

More than 25 years after the death of Zwingli (†1531), the first revision of the Froschauer Bible of 1531 appeared in 1557, which was revised again in 1574 (Info and Faksimiles). From 1589 the verse division was added. It should be noted that in the basic Greek text in Acts 20:7 are 100% the same words as in Mk 16:2; Lk 24:1 and Jn 20:1, so the falsification becomes obvious, because the same words cannot mean two different days at the same time, where everyone can choose a certain one:

Dramatic are the changes in the 1860 edition: in Mt 28:1 the "evening" was simply replaced by "after". In Mt 28:1a the Sabbath was mentioned only once, otherwise it was erased in all places and replaced by the "first day of the week". Especially the changes in Acts 20:7 and 1Cor 16:2 are shocking, where the "one Sabbath" was erased from the Bible:

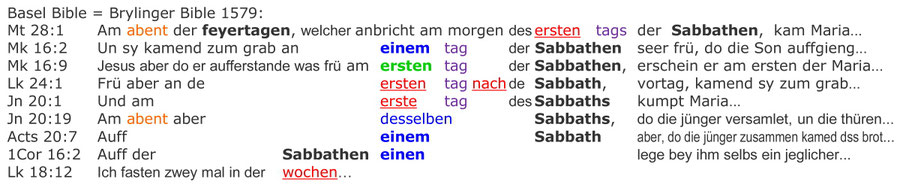

Basel Bible = Brylinger Bible 1579

Nikolaus Brylinger (Erben) printed another NT (Info and Facsimiles) in Basel in 1579. It is a slightly modified version of the text of the Zurich or Froschauer Bible of 1531, which was published by the Zurich Central Library (Zentralbibliothek Zürich) and still contains the Resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath day" and the gathering of the disciples "on a Sabbath". Only in Lk 24:1 the word "after" was added to the Bible, which created a great contradiction to the other verses. For Jesus appeared to the disciples "on the evening of the same Sabbath" (not "on the same Sunday"; Jn 20:19). Who has a problem understanding this statement?

Barther Bible = Pomeranian Bible 1588

When the Duke of Pomerania, Bogislaw XIII (*1544; †1606), resided in Barth (Northern Germany), he commissioned a new print of a Low German Bible (Facsimiles). The text was based on the Bugenhagen Bible of 1533, which was only slightly changed in language. This Bible was produced in an edition of 1,000 copies and was the altar and church Bible in Pomerania (=Pomeranian Bible; Pommersche Bibel). When reading it aloud, all Christians throughout Pomerania could hear that Jesus rose from the dead "early on a Sabbath morning" (Mk 16:2) and appeared to the disciples "on the evening of the same Sabbath" (Jn 20:19). No Christian could find the "first day of the week" or Sunday in the Bible:

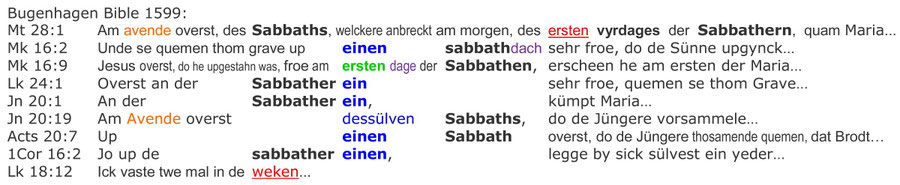

Bugenhagen Bible 1599

A linguistically slightly modified version of the Low German Bugenhagen Bible 1533/34 was published in Wittenberg in 1599 (Info and Facsimiles). Title: "Biblia Dat ys: De gantze hillige Schrifft, Sassisch, D. Mart. Luth., Uppet nye mit flyte dörchgesehen, unde umme mehrer richticheit willen in Versicul underscheiden: Ock na den Misnischen Exemplaren, so D. Luther 1545 sülvest corrigeret, Wittemberch, 1599". Until 1726 numerous editions, especially of the NT, were printed in various German cities. The Sabbath resurrection of Jesus was always preserved. There was never talk of a Sunday. The women came to the tomb "on a Sabbath" and Jesus appeared to the disciples "on the evening of the same Sabbath:

Conclusion

As could be clearly shown, not only the original Luther Bible speaks over several centuries of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" morning, but also all three official Catholic counter- or correction Bibles. In other words: Catholics and Protestants had the same opinion, namely that the women of the Bible came to the grave "on a Sabbath" morning, even if "on a Sunday morning" was preached orally in the service. As could be shown above in the text, the "first Sabbath" always means only the first of the seven Sabbaths up to Pentecost, and never the "first day of the week" or Sunday. Just as there are the second, third and seventh Sabbath until Pentecost, so there is also the "first Sabbath".

Just as everyone understands the phrases "on the first Sunday until Pentecost" or "on one of the Sundays" until Pentecost or "on one of the Sundays of Advent" until Christmas, so also every Christian who knows the calendar of God knows what "on one of the Sabbaths" and "on the first Sabbath" means, i.e. the first of the seven Sabbaths until Pentecost. Mark 16:9 had formulated this extremely clearly: "early on the first Sabbath" (see Interlinear) in the genitive singular. There is only one correct translation for this, and many respected Catholic writers have translated this perfectly into German, although it was against their own church dogma.

So the information given on this website about the biblical true day of Jesus' resurrection is by no means something new, but ancient Christian (Catholic and Protestant) basic knowledge.

Overview: Historical Bibles and the Resurrection Sabbath

Numerous Bibles in many languages teach the resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath morning:

7. Many old Bibles proclaim the resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath or Saturday morning

7.1 Greek Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.2 Latin Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.3 Gothic Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.1 German Bible manuscripts show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.2 German Bible prints 1 (before Luther) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.3 German Bible prints 2 (since Luther) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.4 German Bible prints 3 (since 1600 to 1899) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.5 German Bible prints 4 (since 1900) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.1 English Bible manuscripts show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.2 English Bible prints 1 (from 1526 to 1799) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.3 English Bible prints 2 (from 1800 to 1945) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.4 English Bible prints 3 (from 1946 to 2002) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.5 English Bible prints 4 (from 2003) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.6 Spanish Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.7 French Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.8 Swedish Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.9 Czech Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.10 Italian Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.11 Dutch Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.12 Slovenian Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

"Prove all things; hold fast that which is good. Abstain from all appearance of evil"

(1Thess 5:21-22)

"Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them"

(Epheser 5:11)