- Home

- English

- Structure of the Bible

- Structure of the Menorah

- Ancient Menorahs

- Calendar and Feasts

- Resurrection on Sabbath

- Introduction

- Day

- Sabbath

- High Sabbath

- Pre-Sabbath

- Week

- Interlinear Bible

- Church Opinions

- 1. No Sunday

- 2. A Sabbath

- 3. No Friday

- 4. Intermediate Day

- 5. Three Days and Three Nights

- 6. Manipulations

- 6.1 Sabbath not Sunday

- 6.2 Plural σαββατων not week

- 6.3 one not first

- 6.5 Day of the Sabbaths

- 6.7 Lords Day

- 7. Old Bibles

- Greek Bibles

- Latin Bibles

- Gothic Bible

- English Manuscripts

- English Bible Prints 1

- English Bible Prints 2

- English Bible Prints 3

- English Bible Prints 4

- German Manuscripts

- German Bible Prints 1

- German Bible Prints 2

- Spanish Bibles

- Italian Bibles

- Swedish Bibles

- Czech Bibles

- μια των σαββατων

- Mt 28-1

- Mk 16-2

- Mk 16-9

- Lk 24-1

- John 20-1

- John 20-19

- Acts 20-7

- 1Cor 16-2

- Lk 18-12

- 7 Languages

- Palm Sabbath

- Omer

- Summary

- The Rapture

- Rabbi Kaduri Note

- 666

- 888

- Video

- Info

- Historic Bibles Facsimiles

- Francais

- Deutsch

- Espanol

- Dutch

- Ελληνική

- Pусский

- Introduction

- Day

- Sabbath

- High Sabbath

- Pre-Sabbath

- Week

- Interlinear Bible

- Church Opinions

- 1. No Sunday

- 2. A Sabbath

- 3. No Friday

- 4. Intermediate Day

- 5. Three Days and Three Nights

- 6. Manipulations

- 6.1 Sabbath not Sunday

- 6.2 Plural σαββατων not week

- 6.3 one not first

- 6.5 Day of the Sabbaths

- 6.7 Lords Day

- 7. Old Bibles

- Greek Bibles

- Latin Bibles

- Gothic Bible

- English Manuscripts

- English Bible Prints 1

- English Bible Prints 2

- English Bible Prints 3

- English Bible Prints 4

- German Manuscripts

- German Bible Prints 1

- German Bible Prints 2

- Spanish Bibles

- Italian Bibles

- Swedish Bibles

- Czech Bibles

- μια των σαββατων

- Mt 28-1

- Mk 16-2

- Mk 16-9

- Lk 24-1

- John 20-1

- John 20-19

- Acts 20-7

- 1Cor 16-2

- Lk 18-12

- 7 Languages

- Palm Sabbath

- Omer

- Summary

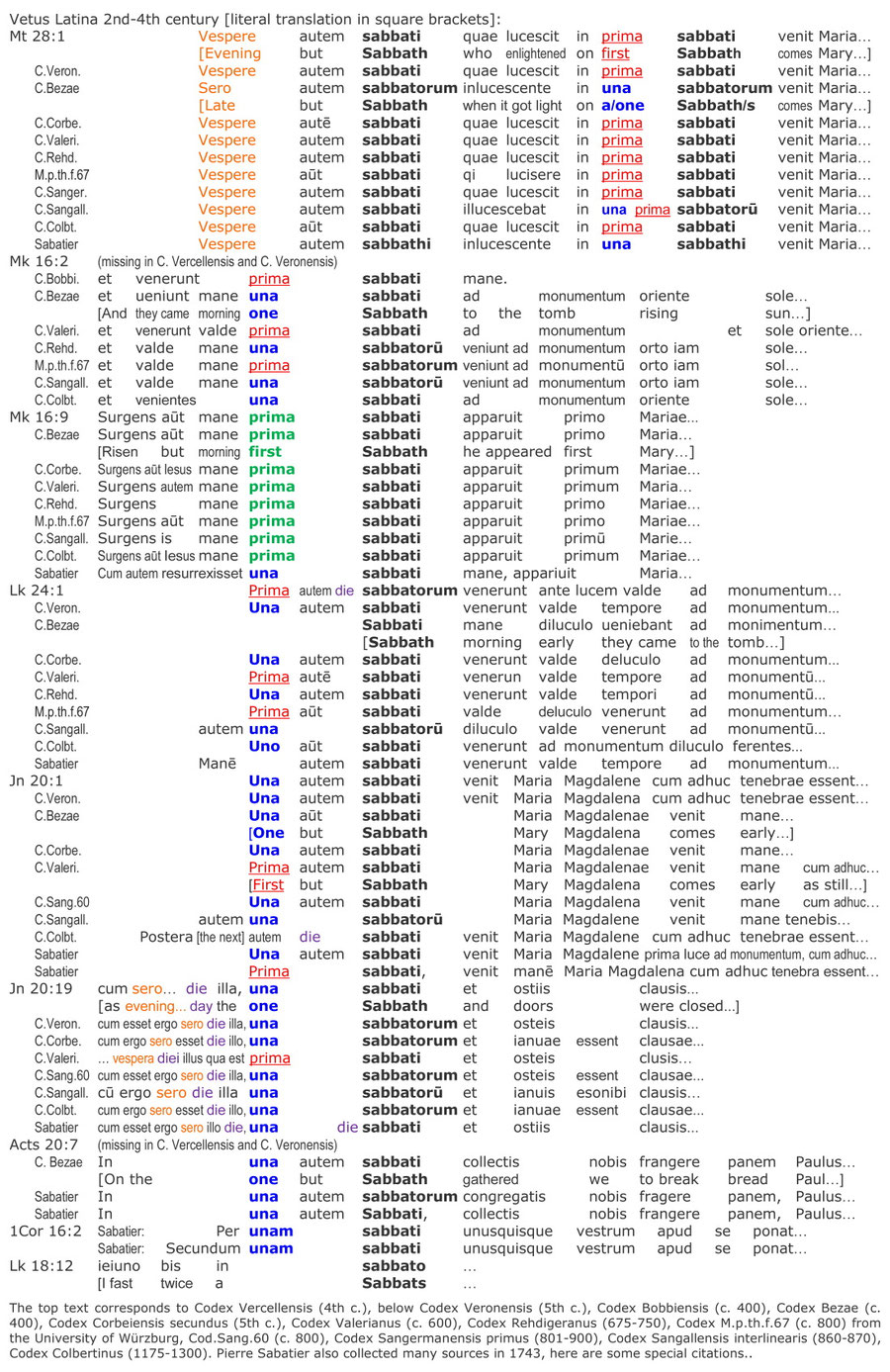

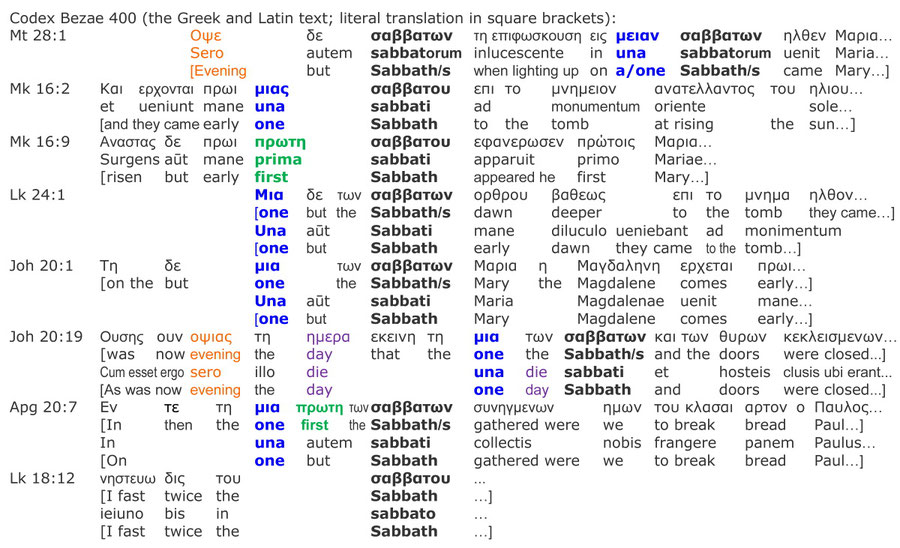

Latin Bibles show the Resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath

The Latin translations of the Greek New Testament (NT) were the most important church texts in the entire Christian world for many centuries. They are of great importance to us because the original Greek was usually very well translated into Latin. It turns out that the evangelists really meant the resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath morning or on a Saturday morning. This is also shown by the many German Catholic Bibles that were translated from the Vulgate.

Vetus Latina 2nd-3rd century

The "Vetus Latina" ("old Latin"), "Vetus Italica" or briefly "Itala" is the name for the oldest translations of parts of the Old Testament (OT) and New Testament (NT) into the Latin language (info and facsimiles). This refers to all Bible texts translated from Greek that do not belong to the Vulgate. They were created since the 2nd century AD and include a variety of different texts. Therefore, the content varies. The oldest surviving manuscripts are Gospel texts from the 4th and 5th centuries (Codex Vercellensis; Codex Bobiensis, only parts Mt, Mk). They are based on translations made at the latest in the 3rd century (cf. Wikipedia). The Latin text of the Codex Bezae (around 400) is the oldest form of the Vetus Latina and has great correspondence with the Codex Veronensis and the Codex Bobiensis. Codex Corbeiensis secundus was copied in Italy in the 5th century, the Codex Valerianus c. 600. The origin of Codex Rehdigeranus 675-750 is northern Italy; an adaptation was made in 1865 by Friedrich Haase (*1808; †1867) of Breslau in Silesia (Latin: Vratislavia). The Codex M.p.th.f. 67 from the Breton or Anglo-Saxon area (Uni Würzburg) dates from about 800. From St. Gall comes the Gospel of John Cod. Sang. 60, which was copied in Ireland around 800. The Codex Sangermanensis primus from 801-900 contains readings of the Vetus Latina in the Gospel of Matthew, otherwise it follows the line of the Vulgate. The Codex Sangallensis interlinearis (860-870) from St. Gall is one of the first true interlinear Bibles. The Codex Colbertinus from southern France was made very late (1175-1300), it is a mixed text, because the Gospels follow the Vetus Latina, the other writings the Vulgate. Pierre Sabatier collected several ancient sources and published them in 1743 (title: "Bibliorum sacrorum latinae versiones antiquae, seu Vetus Italica, et caeterae quaecunque in codicibus manuscriptis et antiquorum libris reperiri poterunt, quae cum vulgata Latina, et cum textu Graeco comparatur, Remi"). Particularly interesting quotations from different codices are shown in the figure below.

The Vulgate translation was produced around 382 AD to make this multitude of unauthorized (non-official) texts obsolete by providing a single official church translation. The Vetus Latina is nevertheless very valuable, because the following examples show that despite the great variety, the content never speaks of “Sunday“, “Lord's Day“, “week“ or the day “after the Sabbath“. There have always been appropriate words of their own for this in the Latin language (see below), even long before the NT was ever written. All translators knew that the Greek text speaks of the "Sabbath" and no other day before or after. Therefore, the Vetus Latina also always uses the "Sabbath" (sabbati, sabbatorum) and no other day. The phrases mentioned in the Greek and Latin chapters on resurrection cannot possibly mean 2 days at the same time. No man can understand why God should speak of "a Sabbath" when he means "not a Sabbath" but "a Sunday"? Always there was only talk about the Sabbath, 7 times in the resurrection chapter and 70 times in the whole NT. The corresponding Latin words for "Sunday", "Lord's Day" or "week", on the other hand, do not exist a single time in the NT, as can be easily demonstrated. The word "inlustrare" means "to brighten up" on the one Sabbath (Mt 28:1) and also "lucescite" means a brightening or shining up. It does not matter whether someone says "on one Sabbath" or "on the first Sabbath" of the 7 Sabbaths until Pentecost, because the Sabbath always remains. In the same way, anyone can say "on a Sunday" or "on the first Sunday" of the 7 Sundays until Pentecost, yet it does not become a Monday. The Vetus Latina is one of many proofs that the resurrection was indeed on a Sabbath morning, as very many translators in diverse places and independently confirm. This is also exactly the literal translation in many old Catholic Bibles, which even speak of Saturday morning and not Sunday morning (see examples). The following is the content of the Vetus Latina with the literal translation in parentheses:

Who claims that "una sabbati" and "prima sabbati" can have the meaning "a Sunday" and "first day of the week", must first tell how then in Old Latin "on a Sabbath" (in genitive singular) and "first Sabbath" should be expressed? Of course, there is only one possibility for this, namely the one that is written in the Latin NT (Vetus Latina and Vulgate). And anyone who sees it differently should also explain why God does not speak of "a Sunday", "after a Sabbath" or on the "first day of the week" in the Greek NT, but exactly 7 times of the "Sabbath" in the singular and plural (e.g. Mt 28:1a; Mt 28:1b; Mk 16:2; Mk 16:9; Lk 24:1; Jn 20:1; Jn 20:19)? The answer clearly, because God means only "a/one Sabbath." And this is exactly the correct translation in the Vetus Latina and the Vulgate. The words "una/prima sabbati" cannot mean "one/first Sabbath" and "one/first Sunday" or "one/first day of the week" at the same time. And who can find here the translation "after the Sabbath"? No one.

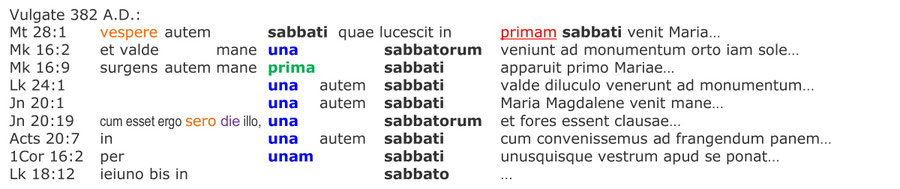

Vulgata Hieronymi 382 A.D.

Since ancient Greek (Koine) was still the common and world language at the time of Jerome of Stridon (*347; †420, Wiki), the translators were experts and knew exactly which words to use and which not (see Wikipedia, Facsimiles, Manuscripts). Therefore it is not surprising that despite the Sunday-sanctification commandment of the Roman emperor and the Roman church, the first official Catholic church Bible nevertheless always reports in all 9 verses only about what happened on "una sabbati" (on a Sabbath). The phrases "after the Sabbath" (post sabbati) or "on the first day of the week" (primus dies hedomadae) or "on a Sunday" (dies solis; solis die) or "on the Lord's Day" (dominicus) were never used in this. Jerome translated what the Greek text really means (and not what some pastors would like), namely, that Jesus was resurrected "on a Sabbath" or "on the first Sabbath":

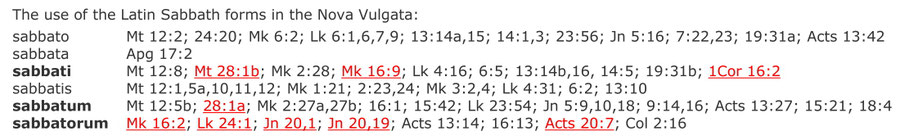

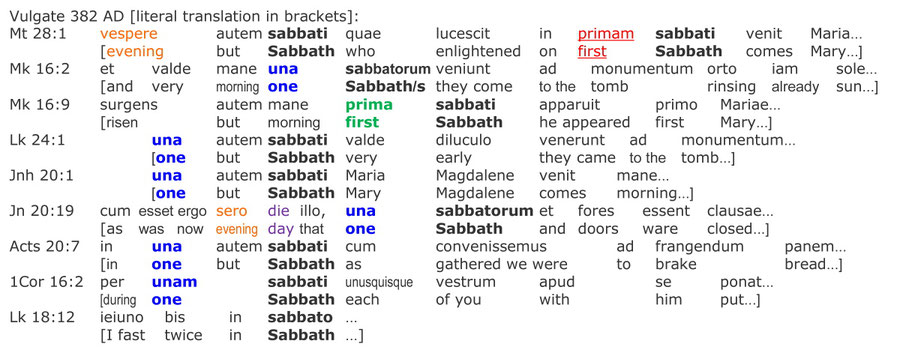

The following figure shows the literal translation:

Again and again theologians and badly educated pastors spread the false doctrine that the Latin text "una/prima sabbati" is supposed to mean "on a Sunday" or "on the first day of the week" or "after a Sabbath"; but this is extremely easy to refute, because these people should just tell us how they would write "on a Sabbath" and "first Sabbath" in the singular genitive into the Old Latin and all discussions will be over so quickly. Besides, there are very many old Catholic Bibles in many languages that have been translated from the Vulgate and tell about the coming of the women to the tomb "on a Saturday" (not: on a Sunday) or "on a Sabbath" (see Old Bibles). The translation was done at a time when Latin was the official language of the Church and all the learned knew exactly what the respective words meant in a national language. They knew the difference between cardinal and ordinal numbers (one/first) and they could also distinguish the Sabbath from a "Sunday" and the "week", because Latin had always had its own words for these. The Latin "week" (hebdomada) is even in the Old Testament (see week) and could have been seen in the New Testament if it corresponded to the basic Greek text. All this is so simple, if also interpretations and falsifications are renounced, because only by the inclusion of church traditions into the Bible it becomes complicated and illogical.

Mt 28,1 - a small mistake with great historical impact!

Jerome has mostly translated very well. He explicitly mentions the "Sabbath" in all verses. Like the Greek text, he also uses the genitive form of sabbath in Latin, namely "sabbati" and "sabbatorum". However, since he did not have an understanding of the biblical order of feast days (see calendar), he had a problem understanding Mt 28:1. If he had known that the basic text spoke only of the transition from the night phase to the day phase on A/ONE Sabbath day, he would certainly have chosen a different wording. But instead of "at the brightening (Greek: τη επιφωσκουση)" he translated "quae lucescit" (which brightens, shines)" and instead of "into a Sabbath" (εις μιαν σαββατων)" he wrote "in primam sabbati" (on the first Sabbath). Thus, altogether an illogical sentence was formed, which confused the Christians. The literal translation of his text is: "but in the evening of the sabbath, which lightens up/shines forth in the first Sabbeth, Mary comes..." This mysterious lighting up or shining forth makes no sense. Since all pre-Lutheran Bible translators (examples), Martin Luther and the Catholic and Protestant theologians afterwards use the Vulgate as text basis, so they (in spite of best conscience and best knowledge of Latin) had to take over inevitably his mistake and have formed all a sentence which no Christian could understand.

Most theologians translated Jerome literally and did not understand that it is not about a lighting up or shining, but about a normal becoming bright on a Sabbath morning. Related words of lucescite (=break on, brighten, shine, illuminate, begin to shine, break daylight) are lux (light), lucere (shine, radiate, become bright), lucet (he/she/it shine), lucesco (begin to shine), and lucescere (break on, brighten, illuminate). So the word lucescit means not only to light up, but also "he/she/it dawns", "becomes bright". In relation to a day, therefore, it speaks only of the passage of the night phase to the day phase: "But in the Sabbath evening, at the dawning of light on the one Sabbath day, Mary came..."

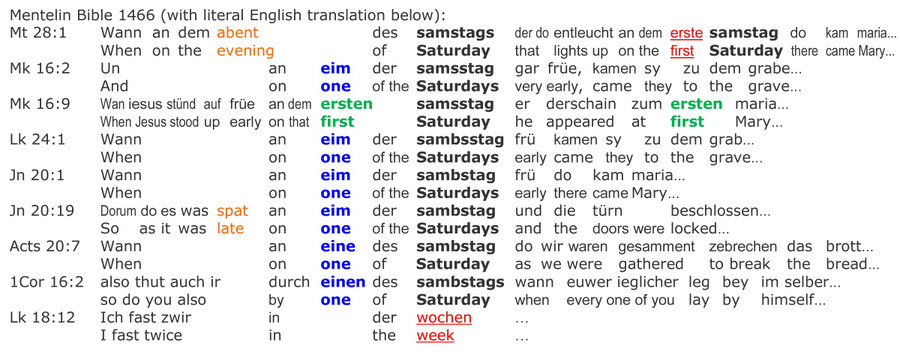

Jerome knew the difference between Sabbath, Sunday, Lord's day and week

Unlike some translators of today, Jerome knew very well the difference between the words Sabbath, Sunday and week, and he knew that the original Greek text did not speak of "on the first day of the week", nor of "on the day after the Sabbath", nor of "on a Sunday", but only of "but on a Sabbath..." (una autem sabbati). Jerome himself knew "hebdomades", that is, the corresponding Latin word for "week", and also mentioned it several times in the Old Testament text itself (see week). But in the NT, as a great expert in language, he spoke only of an event "on a Sabbath". If he had meant Sunday, he would have had many ways to express it. Whoever disagrees and still claims that "sabbati" can also mean "week", "Lord's Day" or "Sunday", should first explain why so many old Catholic Bibles translated the Vulgate correctly and report not only "a Sabbath" morning, but even "a Saturday" morning (see examples). Exactly this is also the statement of the first worldwide printed Bible in a national language (Mentelin 1466). The printing of all the world's Bibles in a national language began with the proclamation of Jesus' resurrection on a Saturday morning:

The fact is and remains: In Latin only one day can be meant and not two days at the same time, where everyone can choose what he wants.

Jerome knew the difference between "one" and "first"

Jerome was also able (unlike many pastors of today) to distinguish μια (mia, one) and πρωτη (prote, first) in Greek and not lump them together. He could differentiate the cardinal numbers (una, duo, tres...) from the ordinal numbers (primus, secundus, tertius...) and translated correctly. Only in the verse in Mt 28,1b, which was difficult to understand for him, he made an exception and replaced una (one) by prima (first), although the basic Greek text speaks of μιαν and not of πρωτη (prote, first). This error, by the way, was corrected by Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1516 (see below). In all other verses Jerome spoke correctly of "una sabbati" (a/one Sabbath) and not of "primam sabbati" (first Sabbath). And in Mark 16:9 he rightly uses the phrase "prima sabbati" (first Sabbath), since the Greek text actually says prote (first) and not mia (one). So he knew that in most places the basic text did not mean "on the first Sabbath" but "on a Sabbath" when the women came to the tomb. However, even if Jerome had translated "prima sabbati" (first Sabbath) rather than "una sabbati" (on a Sabbath) in all places, even then it would still be a Sabbath day, namely the first Sabbath in the count of the seven Sabbaths until Pentecost. It is important to differentiate, otherwise, in the counting until Pentecost, no man could say "on the first Sabbath" (prima sabbati) or "on the second/third/fourth.... Sabbath until Pentecost", because this would then automatically always be "on the first/second... Day of the week" (in primo/secundo... the hebdomadis) or "on the first/second Sunday", which would be absurd. Also in Latin people were able to express themselves clearly. And if the Latin language speaks of the "first Sabbath", then the day after cannot be meant at the same time. This example alone shows that every translator must differentiate exactly between what is written and what is not written.

The Vulgate is a great treasure because it is the first ever official translation of the NT into another language and it has preserved the expression "a Sabbath" which comes from the original Greek. It is important to note that from the time of the apostles until over 1,500 years later, there was hardly a Bible that spoke of the "first day of the week" or the "Lord's Day" or "Sunday" in the 9 verses mentioned. The Catholic Vulgate was the only available Bible in the world and this spoke only of a resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning". The world's first printed book, the 1452 Gutenberg Latin Bible, also proclaimed Jesus' resurrection "on a Sabbath."

Since Latin was the language of the church in all European states, but the common people did not understand it and many could not even read, the Bible remained the preserve of only a small group of studied theologians who interpreted it to the people. In concrete terms, this meant that people were dependent on what the church preached to them in forming their opinions. They knew neither what was in the Bible nor what was not in it. Since the Catholic Church feared for its position of power and wanted to avoid theological disputes and divisions, it was initially not at all interested in having the Bible translated into the respective national languages. In addition, it was also a question of cost. Since all Bibles had to be laboriously copied by hand, they were correspondingly rare and very expensive and unaffordable for ordinary people. Today, every Christian can even have many Bibles and is not even aware of what a great treasure he holds in his hands.

Jerome did not cause an accident with the choice of his words, but he translated the basic Greek text (with the exception of a few passages, e.g. Mt 28:1b) as it had to be. His work is a cautionary example to all translators after him, and many of them even translated his words correctly into other languages. Even the new Catholic Public Domain Version (CPDV), translated from the Vulgate into English and published only in 2009, always mentions "Sabbath" (Sabbath) in all places and never "week" (week) or "Sunday" (Sunday). This is one of many examples that even today's Catholics admit that the resurrection of Jesus had to have occurred biblically "on a Sabbath," even if the churches wish for a different day.

The word "Sabbath" does not originate from the Latin language. It is a foreign word from Hebrew, which was absorbed into the Greek and Latin languages. When people adopted this name into their own national language, they did not do it in the long version "dia sabbati" (day Sabbath, Sabbath day), but in the short form sabbati (Sabbath). If you type "a Sabbath" into a translation program, you get "una sabbati" or "sabbatum". The Sabbath was seen in the feminine sense in Greek and Latin, so the feminine primam and not primum or primus precedes the Sabbath.

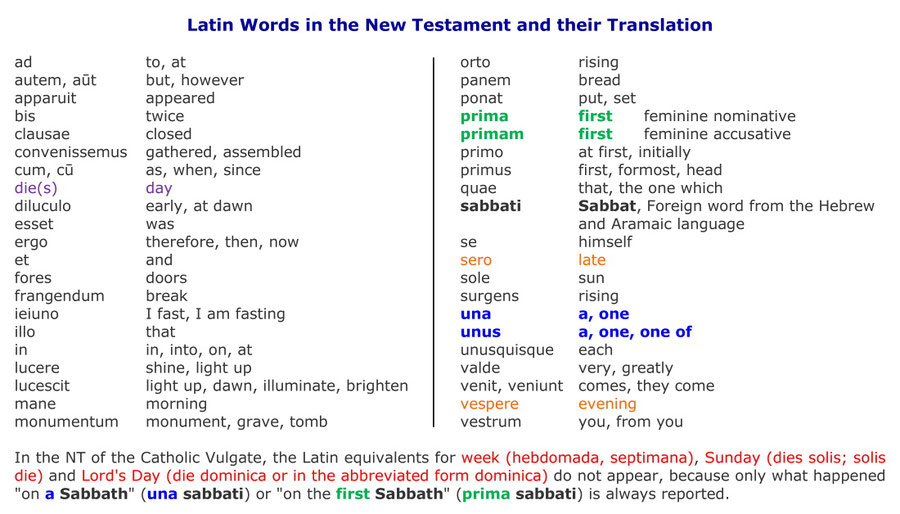

There are many dictionaries that make clear the differences between Sabbath, Sunday, week, one, first in Latin (e.g., www.frag-caesar.de). Although the Latin language has also changed over the years (e.g., in grammar), the word meanings have not changed. Some dictionaries claim that "sabbatum" can supposedly mean "week." However, this is not done out of any logical linguistic necessity, but only to implement the Sunday doctrine in the translation programs, otherwise the Sunday resurrection could be questioned. The Latin language has always been able to differentiate clearly and there are only insignificant differences to the Old Latin in our context:

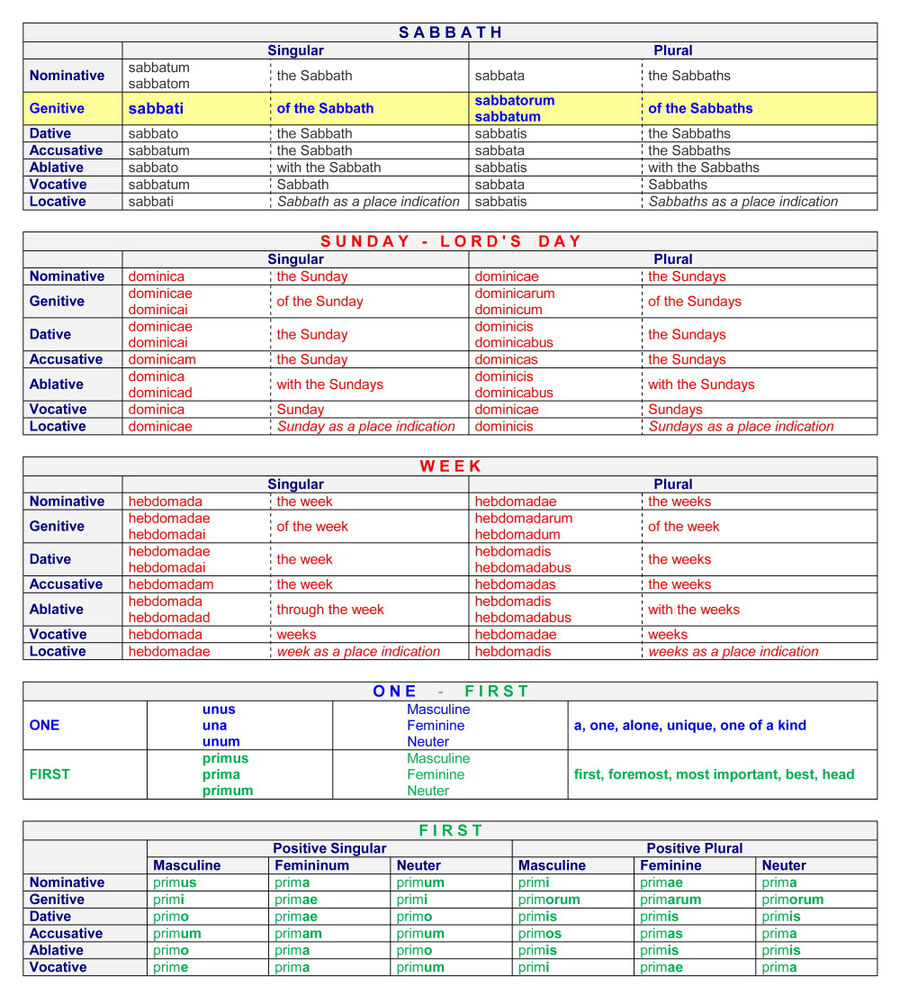

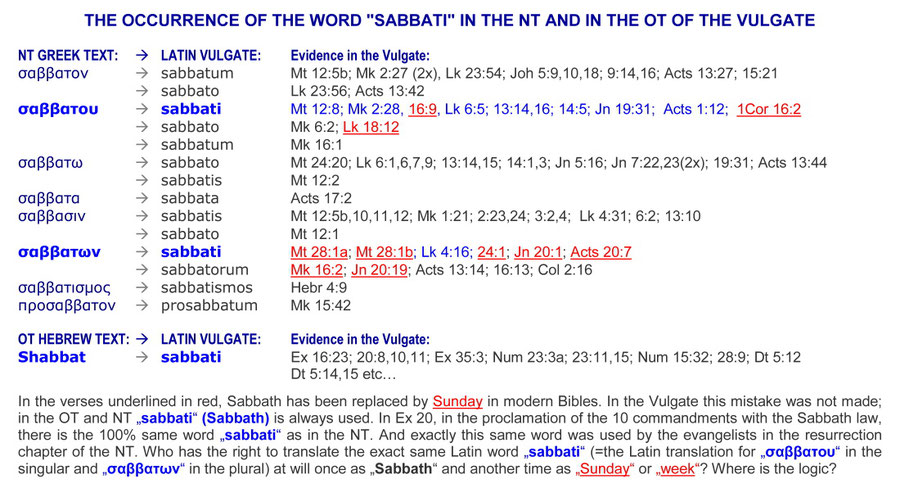

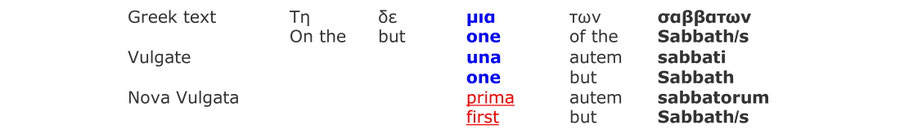

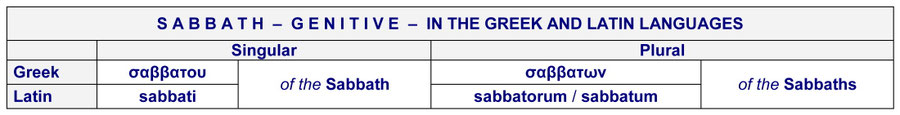

The Latin translation of σαββατου and σαββατων

The Jerome Vulgate, in translating the Greek words σαββατου (singular) and σαββατων (plural), most often uses the word sabbati in the singular (Mt 28:1a; 28:1b; Mk 16:9; Lk 24:1; Jn 20:1; Acts 20:7; 1Cor 16:2), further sabbato (Mk 6:2; Lk 18:12) and the plural sabbatorum (Mk 16:2; Jn 20:19, etc. ). The use of these grammatical forms in the other passages of the NT clearly proves that in fact only "a/one Sabbath day" was meant in each case, and never any other day of the week. In the OT the Vulgate used the word (h)ebdomada (week) 21 times (see chapter Week). So Jerome could well have spoken of the "first day of the week" in the NT if he had wanted to. But he translated correctly. The ancient Greek and Latin language do not contradict each other in their statements:

As can be clearly seen, the word "sabbati" was often used in the Vulgate in the Old Testament (OT) when it came to the translation of the Hebrew Shabbat in the singular, e.g. when God had proclaimed the 10 Commandments. If you read these passages in the OT of the Vulgate carefully, you will immediately realize that the translator in the NT never meant anything else by the word "sabbati", except always "a Sabbath". For Jerome, the Church Father of the Catholic Church, it was thus clear that both the resurrection of Jesus and the meeting of the Christians took place biblically in each case "on a Sabbath," even if Church tradition taught otherwise.

If the basic Greek text mentioned the Sabbath genitive in the plural "σαββατων", Jerome nevertheless often used the corresponding Latin "sabbati" in the singular. This is entirely correct. In contrast to today's theologians, Jerome knew both languages since childhood and knew quite well that according to special language rules in the ancient Greek language with the plural σαββατων very often only a Sabbath day in the singular was meant. Thus, in 6 verses he spoke not of the sabbatorum, but of the "sabbati" (Mt 28:1a; Mt 28:1b; Lk 4:16; Lk 24:1; Jn 20:1; Acts 20:7). It is the 100% same word we find in Ex 20:8-11. So Jesus' resurrection day is about exactly the same Sabbath day (last day of the week) as in the time of Moses.

The phrase "μια των σαββατων" has been translated in the Vulgate as "una sabbatorum" (Mark 16:2) or "una sabbati" (see Luke 24:1; John 20:1; Acts 20:7) in 4 biblical passages. This literally means "on a Sabbath" in the singular (genitive). It does not mean "on the day after the Sabbath," nor does it mean "on the first day of the week," nor does it mean "on a Sunday," for even the Latin language has its own equivalents for this.

If the translators of today would translate the Greek original text into Latin, then they would have to invent (in order to support their Sunday theory) in the 8 Bible verses in each case completely different Latin sentence positions, which Jerome never used. And if they were to translate the Vulgate back into Greek, they would also have to invent completely new Greek phrases that were never in the ancient Greek basic text. So if someone wants to translate the Vulgate into English or German, he will not get "on a/first Sunday" nor "on the day after the Sabbath" nor "on the first day of the week". And it immediately becomes clear to him that God must have meant only the resurrection Sabbath.

The church leadership, contrary to the Word of God (!), preached to ordinary Christians that Jesus was not resurrected on the Sabbath, but on Easter Sunday, just to establish a different pagan calendar. For the Catholic Church, Easter Sunday was only enforceable because of Jesus' resurrection. Therefore, from the beginning, the foundation of Sunday sanctification was never built on facts from the original Greek text or the Latin translation (Vulgate), but only on the desire of state and church leaders who wanted to sanctify the pagan day of the sun (Sunday). The Christians were to be kept stupid. Therefore, it was not desired that the common people read the Bible and it was claimed that only studied theologians could understand the Bible. But according to 1Cor 1:26 God called just simple people who accept the word of God as it is and can very well distinguish "on a" from "after a" Sabbath.

Who is still of a different opinion should simply translate the phrases "on the Sabbath" or "on a Sabbath" (in the genitive) or "on the first Sabbath" (in the genitive) into the Old Latin and will realize at the latest then that there are not many possibilities for this and that it corresponds to the text of Jerome. His words are clear and unambiguous and many Catholic, Protestant and free-church Bible translators have also correctly translated this into other languages (see Old Bibles).

The phrase "una sabbati" cannot mean "on a Sabbath" and "on a Sunday" or "on a first day of the week" or "after a Sabbath" at the same time. This has never been so in any language of the world.

The Latin Sabbath in the Singular and Plural

The Latin words "sabbati" and "sabbatorum" of course also does not mean "week" or "Sunday" as some would like, but it is nothing else than the singular "Sabbath" and plural "Sabbaths" in the genitive form, since the Greek also often uses the genitive. Just the use of the 100% same "sabbati" and "sabbatorum" on other verses of the OT and NT makes this fact very clear. Not only in the Vulgate and other Latin translations does this word appear, but also in extra-biblical literature.

Singular Sabbath (sabbatum) in Latin and English:

Nominative: sabbatum, sabbatom = the Sabbath

Genitive: sabbati = of the Sabbath

Dative: sabbato = the Sabbath

Accusative: sabbatum = the Sabbath

Ablative: sabbato = with the Sabbath

Vocative: sabbatum = Sabbath!

Locative: sabbati = Sabbath as a locative

Plural Sabbaths (sabbata) in Latin and English:

Nominative: sabbata = the Sabbaths

Genitive: sabbatorum, sabbatum = (of) the Sabbaths

Dative: sabbatis = the Sabbaths

Accusative: sabbata = the Sabbaths

Ablative: sabbatis = with the Sabbaths

Vocative: sabbata = Sabbaths!

Locative: sabbatis = Sabbaths as place names

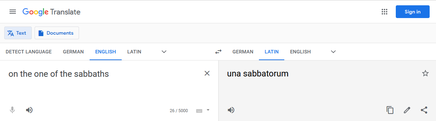

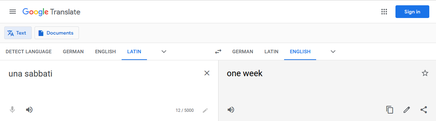

Note on the Translation of the Word "sabbati" in Language Programs

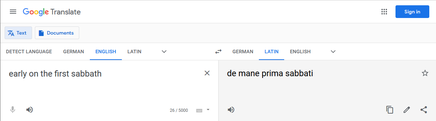

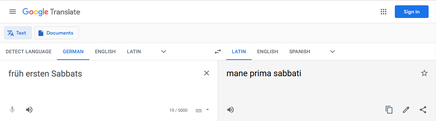

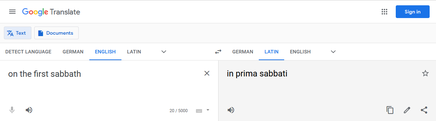

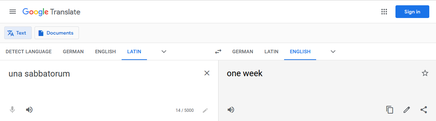

If you want to know what Jerome really meant in his translation (Vulgate), you have to work with professional dictionaries or with language experts. If you type in online Google translation "una autem sabbati", you sometimes get as a big surprise the words "a weekday" and then again even "on Sunday morning" or "early on Sunday". But the word "sabbati" means "Sabbath" and not "Sunday" or "week", because Latin has two words of its own for that, namely "hebdomada" and "septimana", both derived from the sevenness or a series of seven (see week). The Latin "una" means "one", "autem" means "but/however" (not "early") and "sabbato" means "Sabbath", a word which occurs very often in the Old and New Testaments of the Vulgate and never means "Sunday". So how can "but on a Sabbath" (una autem sabbati) all at once make "early on a Sunday"? That is impossible. So no human being could say "on a Sabbath" in the old Latin language? Here it becomes clear how chaotic and contradictory the programming of the translation is. Everything is tried to make a Sunday out of a Sabbath. The phrase "early first Sabbath" means "mane prima sabbtati", but then the same should also mean "on Sunday morning" or "the first week"? No, definitely not. The Google translation program is completely unsuitable for translating the Vulgate.

Then the question arises, why does the input of "una autem sabbati" then not come out "but on a Sabbath/Saturday"? The answer is simple: it becomes apparent that some systems have been programmed to learn how people have done a translation of other texts, or how they would like it to be done. And the Bible (Vulgate) is one of the most famous sources. Moreover, in Old Latin there were some idioms that are not even considered in New Latin programs. Therefore, it may happen that no one gets "una autem sabbati" no matter how hard he tries. On the other hand, if you enter the word "week", you will get the correct Latin translation, namely septimana, septem, hebdomana or hebdomas, but quite correctly NOT sabbati. Other phrases that have nothing to do with the Bible are translated correctly, like "mane die sabbati" = "Saturday morning". But the "early first Sabbath" translated literally from the basic Greek text in Mk 16,9 results in "mane prima sabbati" very correctly in Google translation. But who again enters "mane prima sabbati" gets to the surprise not again "early first Sabbath", but "early Sunday" or "on Sunday morning", which really can only be endured with a lot of humor. Sabbath became Sunday and there is no way to come to the Sabbath?

The Greek version of Google Translator, on the other hand, is much better and often speaks of "a/one Saturday morning" after entering the Greek text (see examples). According to www.frag-caesar.de the Latin "week" is expressed by the nouns hebdomada, hebdomadis, hebdomas and septimanusa and not by "sabbati". This is clear because the latter is the frequent designation of the clearly defined 7th day of the week in the Hebrew calendar (from sunset on Friday to sunset on Saturday).

It should always be noted that there is no genitive in the English language, so it is never possible to translate correctly from English into Ancient Greek or Ancient Latin. In the German language, this is all much easier, because the grammar is structured similarly. In this case, translating from the basic languages into German and translating back into the basic languages always gives the same result. This is not possible in the English language. That is why there are so many German Bibles that have been translated correctly over the centuries (see German Manuscripts, German Bible Prints 1).

Codex Bezae 400 AD

The Codex Bezae, also Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis is a manuscript of the NT in Greek and Latin from the 5th century (Wikipedia; info and facsimiles). This was the only biblical text from the first millennium known to the reformers in the 16th century. The codex takes its name from Theodore Beza, the successor of John Calvin. The codex contains the four Gospels in the order of the Western manuscripts (Matthew, John, Luke, Mark) and part of the Acts of the Apostles. It consists of 415 leaves inscribed in a single column (26x21.5 cm). The left side of each is Greek, the right Latin. The Latin text is the oldest form of the Vetus Latina and has great correspondence with the Codex Veronensis and the Codex Bobiensis, but has some important peculiarities. The content is very important, because it shows that in Mt 28,1a actually the evening (sero) was meant and not "after the Sabbath". In Mt 28:1b even the Vulgate error was corrected ("a/one Sabbath" instead of "first Sabbath"). In Lk 24,1 the words one/first are completely omitted, it simply says "Sabbath morning" (sabbati mane). This is understood by every child. For the specifics in the Greek passage, see link. The following illustration shows both original texts with the respective literal translation in brackets:

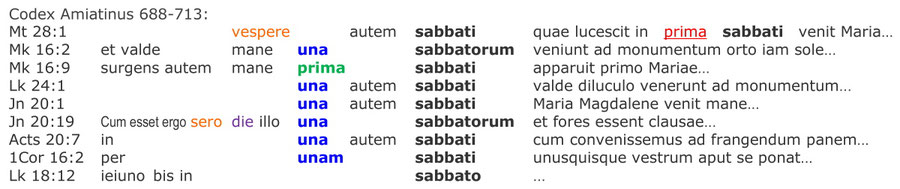

Codex Amiatinus 688-713

The Codex Amiatinus (688-713 AD) is the oldest extant text of Jerome's complete Bible (info and facsimiles). It is also considered the most accurate text of Jerome's translation until the revision by Pope Sixtus V in 1585-1590. The codex also contains a plan of the Tabernacle in the Temple of Jerusalem (see illustration at 688 AD). What is the content? The Sabbath resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ:

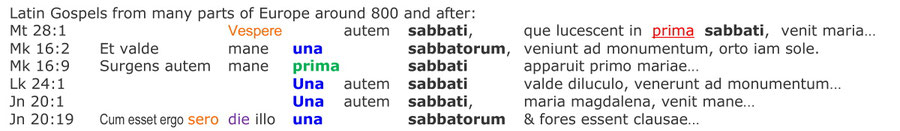

Latin Gospels from around 800

In addition to entire Bibles, a great many individual manuscript gospels with the Vulgate text were produced throughout Europe. The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich publishes facsimiles from several centuries (https://opacplus.bsb-muenchen.de search word "Evangeliar", see also Facsimiles). It shows a sensational purple gospel book (Evangeliarium purpureum) from the first quarter of the 9th century (Clm 23631) with purple leaves and golden writing and other Bibles owned by rulers. The gospel book of Otto III. (Clm 4453) with a splendid binding and luxurious decoration (precious stones, pearls, ivory) was commissioned by the emperor. The Evangeliary of the Sainte-Chapelle from 983 is one of the main works of Ottonian book illumination. The manuscript is in Paris (Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 8851). The Reichenau Gospels of Henry II (BSB Clm 4454) is also lavishly decorated and has a cover with precious stones and pearls and is considered one of the most magnificent works of the Ottonian period and an outstanding testimony to medieval artistry. These are very expensive books of kings and emperors. An example, Wikipedia writes (translated):

"Otto III. (*980; †1002), of the house of the Ottonians, was Roman-German king from 983 and emperor from 996.... Henry II (*973; †1024), saint (since 1146), of the noble house of the Ottonians, was duke of Bavaria as Henry IV from 995 to 1004 and again from 1009 to 1017, king of the East Frankish Empire (regnum Francorum orientalium) from 1002 to 1024, king of Italy from 1004 to 1024, and Roman-German emperor from 1014 to 1024."

And what does it say in all these gospels? Answer: that Jesus was resurrected "on a Sabbath morning" (una sabbati) or on the "first Sabbath" (prima sabbati) until Pentecost (Mt 28:1; Mk 16:9) and not "on a Sunday":

Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram around 879

The Codex Aureus (Latin: "golden book") is a designation of various works of book illumination, which were made with gold ink and were therefore particularly precious (Facsimiles). Among them are several Latin gospels. They belong to the most important book treasures of the Middle Ages. And what do they proclaim? The resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath," of course. The Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram from 879 from the West Francia is also called the Golden Gospels of Charles the Bald (BSB Clm 14000). This magnificent book was written from 870 by the brothers Berengar and Luithard on behalf of Charles the Bald and kept in the Benedictine monastery of St. Emmeram in Regensburg. The front cover is made of chased gold, precious stones and pearls. Charles II. (Charles the Bald; German Karl der Kahle, French Charles II dit le Chauve; *823; †877), of the noble family of the Carolingians, was West Frankish king from 843 to 877 and king of Italy and Roman emperor from 875 to 877. He was able to find the Sabbath in the NT:

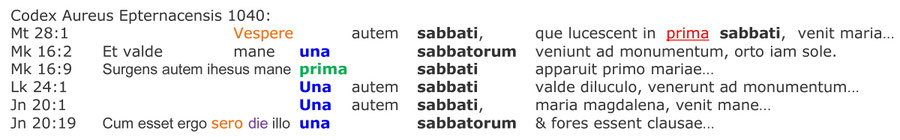

Codex Aureus Epternacensis 1040

The Golden Gospels of Echternach (Latin Codex aureus Epternacensis or Codex Gothanus) was created around 1040 near the diocese of Trier (germany), in the Benedictine Abbey of Echternach in present-day Luxembourg, the most important scriptorium at that time (Facsimiles). The book cover is a masterpiece of the goldsmith's art of Trier. It was made of gold, ivory, enamel, precious stones and pearls already around 985/990. The codex was created for use in the Echternach monastery and it remained there until the French Revolution. In 1801, Ernst II. Ludwig of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (*1745; †1804), the sovereign of the Thuringian Duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, bought the codex. Today the book is in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg. The text is the same as all the other Gospels from Europe and that from 879 and is easy to translate. Mark 16:9 speaks of "early on the first Sabbath" (mane prima sabbati) and this is completely correct, because it is about the first of the seven weekly Sabbaths until Pentecost:

Giant Bible of Henry IV 1060

Henry IV (*1050; †1106; Wikipedia) was the eldest son of Emperor Henry III. (*1017; †1056) and the empress Agnes (*1025; †1077). He was co-king in 1053, Roman-German king from 1056, and emperor from 1084 until his abdication on December 31, 1105, forced by his son Henry V (*1081?; †1125). Henry came to the throne as a minor and was the last king of the Roman-German Middle Ages. In a dispute between spiritual and secular power, he was succeeded by Pope Gregory VII. (*1025?; †1085) excommunicated. Henry IV became famous for his walk to Canossa in 1077 (Wikipedia), where the king submitted to the pope and begged his forgiveness. The full Bible of Henry IV. ("Bibliorum veteris Testamenti pars secunda... Libri novi Testamenti") was also called the Giant Bible (facsimiles of the Bible) because of its dimensions (66 x 43 x 12.5 cm; 275 parchments). Just like the previous King's Bibles, this one tells of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" (una sabbati/sabbatorum), namely "early on the first Sabbath" (mane prima sabbati) of the seven weekly Sabbaths until Pentecost. The church meeting also takes place "on a Sabbath":

The Codex Gigas is one of the largest handwritten books in the world (hence the name Gigas, Greek for "giant"). The Giant Bible was probably written in the early 13th century in the Benedictine monastery of Podlažice in Bohemia and is also known as the Devil's Bible, which comes from a famous full-page illustration of the devil on fol. 290r in the codex. The book is written in Latin. About half of the codex is taken up by the copy of the complete Bible, largely according to the Vulgate, while Acts and Apocalypse follow a pre-350 translation of the Vetus Latina. According to a legend, the essence of which is already discernible in a 1635 catalog entry, the codex was written by a monk who was said to have broken the rules of discipline and was therefore condemned to be walled up alive. In order that this severe punishment be remitted to him, he promised to write a book in praise of the monastery in a single night, which would contain all human knowledge. Near midnight he realized that he could not complete this task alone and sold his soul to the devil. The devil completed the manuscript, and the monk added the image of the devil, thus indicating the true author (see Wikipedia). That means concretely, even the devil does not teach in this Catholic work (facsimiles) that according to the Bible Jesus supposedly rose "on a Sunday", but "on a Sabbath" (una sabbati) and "early on the first Sabbath" (mane prima sabbati). In Luke 24:1 even "una" (a/one) is missing, it means in clear words "early but Sabbath" (that is: "early on the Sabbath"), which every child understands:

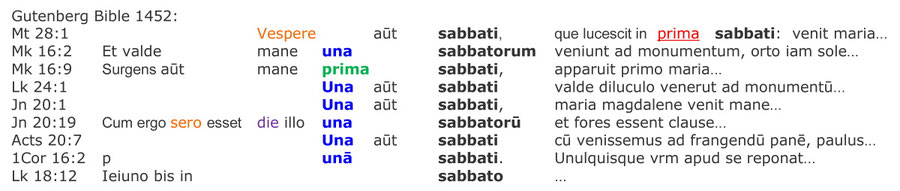

THE WORLD'S FIRST PRINTED BOOK

The world's first printed book was the Gutenberg Bible 1452-1454 (Facsimiles, Wikipedia). Johannes Gutenberg (*1400, †1468; Wikipedia) from Mainz on the river Rhine (Germany) invented the printing press with movable letters. This made it possible for the first time to produce large quantities of Bibles cheaply and quickly in a very good quality. Gutenberg initially printed a few small writings, but the first major work was the Bible. Between 1452 and 1456, 180 copies of the 42-line Bible were painstakingly produced. Paper was used for production, but 40 to 50 copies were printed on very expensive parchments (animal skins). The world-famous Gutenberg Bible was nothing other than the printed version of the Latin Vulgate, which had been widely used until then. In this Catholic Holy Scripture, both the resurrection of Jesus and the meeting of Christians each took place "on a Sabbath" (una sabbati). There was never any mention of a "first day of the week," a "day after the Sabbath," or "on a Sunday." So this means concretely that the world's first and at the same time most famous printed Bible knows only the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning". The following is the text of the Catholic Gutenberg Bible of 1452 with the literal English translation below:

The following tabular presentation makes it even clearer which resurrection day we are really talking about here. All 4 evangelists agree and do not contradict each other. They have given us 7 times the name of the day of Jesus, namely Sabbath. Whoever erases the Sabbath from the Bible and replaces it with Sunday is foolish, because the Latin text is very easy to translate into any language in the world, and the very many old German Catholic Bibles make it clear that the women came to the tombs "on a Sabbath" or "on a Saturday morning" (see English manuscripts; German manuscripts, Prints 1). The Catholic translators of his time grew up with the Latin language, they were experts and knew that the Vulgate speaks of Saturday morning. Even if orally in the church Sunday was preached as the so called "Christian Saturday/Sabbath", in writing it said "a/first Sabbath" (una/prima sabbati), the only way to describe in ancient Latin the Sabbath in the singular genitive:

As can be clearly seen, the history of all books and Bibles printed worldwide in all languages began with the proclamation of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath". This is the Gospel that was exported from Germany to the whole world.

Since Johannes Gutenberg did not have the original Greek text, he could not improve the small translation error of Jerome (e.g. in Mt 28,1b). This is also not tragic, because he reports in all other passages about the coming of the women "on a Sabbath", respectively "on the first Sabbath" (Mk 16:9) of the 7 Sabbaths until Pentecost and not "on a Sunday" (dies solis or dies dominica) or "on the first Sunday" (prima dies solis or prima dominica) until Pentecost. This is not the opinion of a particular church or sect, but the official text of the Catholic Church at that time for many centuries. The Gutenberg Bible is a cautionary example to all translators and to all pastors worldwide that the Greek text can be translated correctly if it is really wanted. With regard to the resurrection Sabbath, we are not dealing here with a new doctrine, but with ancient basic Catholic knowledge. This is the text of the first printed book in the history of the world. And the first Bible, written in a national language worldwide (Mentelin 1466), even speaks of the women coming to the tomb "on a Saturday" (not "on a Sunday") morning and Jesus appearing to the disciples "on the evening of the same Saturday" (John 20:19) when they were gathered in the house. The first Bible printed in a national language in all of America (Saur Bible) also speaks of "a Sabbath morning" and even the first printed Spanish Bible of America (Jünemann) has the same content. The preaching of the Gospel began with the proclamation of Jesus' resurrection "on a Saturday/Sabbath." These are historical facts that no one can deny.

The Passio Domini nostri Jesu Christi 1506 by Johann Geiler

The preacher Johannes Geiler of Kaysersberg (*1445; †1510) wrote a bilingual summary of the Gospels in Latin and German (see facsimiles). As for Martin Luther, it was perfectly clear to Geiler that the Vulgate could only mean the resurrection Sabbath. Especially Mk 16:1 clearly shows that the women bought the ointments "when the Sabbath was past" and afterwards they came to the tomb "on a Sabbath morning". This is understood by everyone who knows that there are always 3 Sabbaths in the Passover week (see illustration). The others don't understand anything at all, start to interpret and have to exchange the biblical words with unbiblical ones to find their desired Sunday in the Bible. Even if in Mt 28,1 the "first" instead of "one" Sabbath is mentioned (as the basic Greek text says), in this case it is not a problem at all, because in that case it is actually the first of the 7 Sabbaths until Pentecost, which were counted every year and are still counted today. This is also confirmed in Mark 16,9:

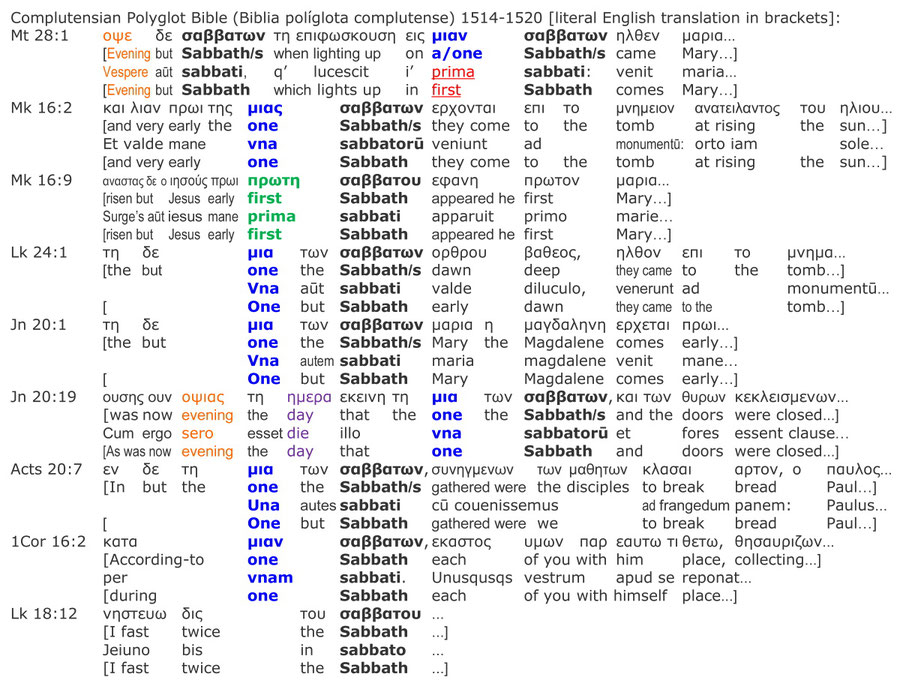

Complutensian Polyglot Bible 1514-1522

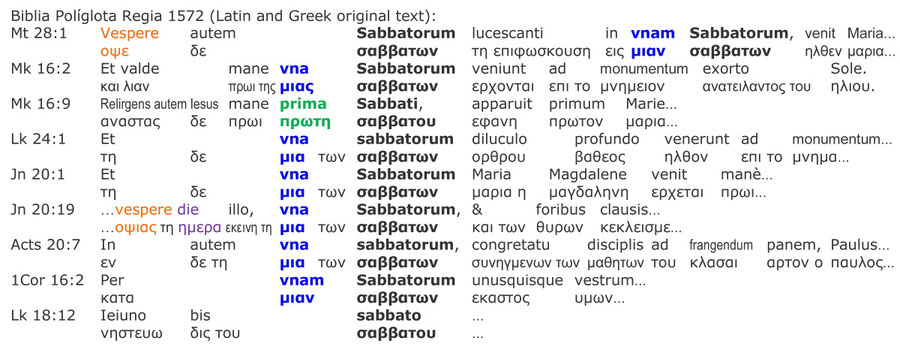

The Complutense University of Madrid (info and facsimiles) published a Bible in several languages, financed by Cardinal Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros (*1436; †1517), starting in 1514. It contains the Hebrew text of the OT (4 volumes), its Greek translation (Septuagint), and the text of the Vulgate. The New Testament (1 volume plus 1 volume dictionary) consists of the Greek text and the text of the Latin Vulgate. The Greek version was prepared by the scholars in Alcalá from a large number of originals and contains the Greek text known at that time. In this official Spanish Catholic parallel Bible, the resurrection of Jesus is clearly stated in both the Greek and Latin texts to have occurred on "una autem sabbati" (on one but Sabbath) and "mane prima sabbati" (early on the first Sabbath; that is, the first of the seven Sabbaths until Pentecost).

The Complutensian Polyglot Bible (Biblia políglota complutense, Complutensian Polyglot) 1514 (NT) is the first printed edition of the Greek NT, but the Erasmus of Rotterdam's version becoming more widely known from 1516 and in 1633 the famous actual Textus Receptus came out. All of these texts belong to the same Byzantine text tradition or text family. The Complutense Polyglot is also the first multilingual printed edition of the entire Bible, and it teaches that Jesus was resurrected "on a Sabbath." Some theologians liked to translate "una sabbati" as "on the first day of the week," but that's impossible because there are entirely different words for that in Latin (see week). And asked the other way around, what else would it have been in Latin if someone really meant "on a Sabbath" (singular genitive) in Latin? Of course as it is written in this Bible:

The following is the same text with literal English translation of the Greek and Latin basis:

Textus Receptus by Erasmus of Rotterdam 1516

Over the centuries, the Vulgate has been copied by hand many times all over the world. Since some copyists had poor or incomplete originals, small errors crept in regionally, which in turn were copied again and again. Therefore, Vulgate texts can be found regionally which differ somewhat in their sentence positions. But with regard to the day of Jesus' resurrection, all manuscripts were in agreement. Moreover, over the years, new translations of the Greek into Latin in a modern linguistic form also developed. One of these was the translation by Erasmus of Rotterdam (*1466-69, †1536), who in 1516 published a bilingual version in which he first printed the Greek text and next to it his Latin text (Novum Instrumentum omne, Facsimiles). He was mainly concerned with the publication of the Greek text, but it is the Latin section that gives us further assurance, because it shows that he really understood what the Greek content was saying and what it was not. Erasmus had mainly economic interests in the publication. Not all the basic Greek texts were available to him and he was pressed for time. Therefore, the first version contained several errors in both the Greek and Latin sections of the text. He even had to translate the missing Greek passages from Latin back into Greek so that the NT would not contain any gaps. Scholars who used his version as a basis for their translation into other languages thus had to automatically adopt all his errors into their own language. Erasmus corrected many errors in his later editions. But there were no errors in the resurrection chapter. He also speaks of what happened "on a Sabbath day" (uno die sabbati/sabbatorm) in each case. Jerome and Erasmus could clearly distinguish one (una) and first (primo), but in the 1519 edition Erasmus introduced the word primo (first) into the NT in Mk 16:2; Jn 20:1 (1541 edition was correct in Jn 20:1). While this is not literally transcribed, it is still completely correct in content, since this Sabbath is indeed the first of the 7 weekly Sabbaths until Pentecost. But on the other hand he translated (in contrast to Jerome) Mt 28,1b literally correct as "una sabbatorum" (one Sabbath, instead of first Sabbath):

The following figure shows the Greek Textus Receptus (see Greek Bibles and the Resurrection Sabbath) with the literal translation and the Latin text by Erasmus. It becomes clear that there are no contradictions between the languages. If God had meant another day, he would have said so. Instead, he mentions the "one Sabbath" or the "first Sabbath" 7 times. The 7 is the number of completeness. The Greek and Latin words for "Sunday" and "week", on the other hand, occur 0 times in both languages:

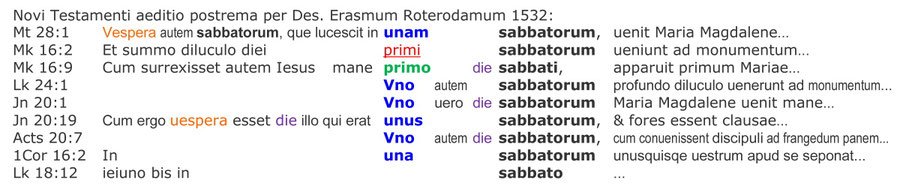

Erasmus NT - Novi Testamenti Aeditio Postrema 1532

The Latin NT of Desiderius Erasmus of Rottedam (* around 1466-69; †1536) was reprinted as final version (Latin: postrema) in 1532 in Basel and 1541 in Zurich (Tiguri) by Christoph Froschauer (* around 1490; †1564), whereby the text of Erasmus was not exactly taken over, but was improved in spelling and translation (see facsimiles). More attention was paid to the grammatical form in the basic Greek text, which is why the Latin "unam" (one) instead of primam (first; as Jerome translated) appears completely correctly in Mt 28:1. The word "sabbatorum" is the plural genitive of "sabbath" (sabbato) and occurs in other places such as Lk 4:16; Acts 13:14; 16:13). Mark 16:9 has also been well translated "early first day Sabbath" in the singular genitive form, which is also found in many other verses in the NT as well. So it is about "a Sabbath", not "a Sunday":

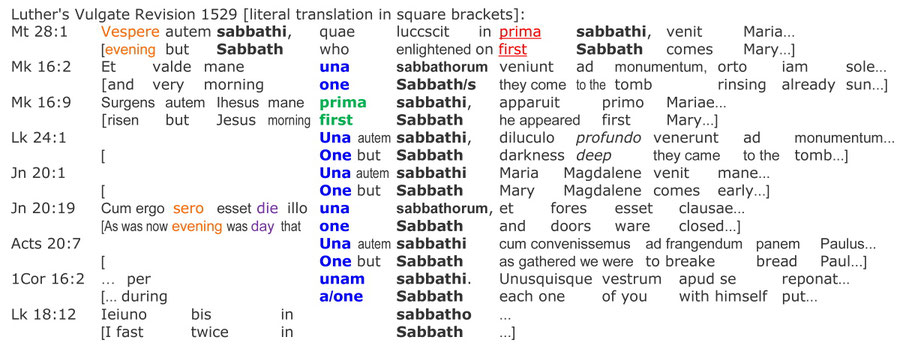

Martin Luthers Vulgate Revision 1529

Since the Latin language also changed over the centuries, Martin Luther brought out a revised (corrected) version of the Vulgate in 1529, which was printed in Wittenberg (facsimiles). It was called the Wittenberg Vulgate Revision. A collaboration with Melanchton is assumed. The goal was to edit the text so that it could be easily understood by Latin speakers. This edition included the entire NT. The Old Testament scriptures were incomplete due to time constraints. Luther's Latin Bible had not gained as much importance (in contrast to the German language edition) because many different Vulgate versions were already established in Europe. Nevertheless, his work is very interesting and is an example to all translators worldwide of how to translate the original Greek text into another language. Martin Luther, who knew the Greek text intimately, did not speak of the "first day of the week" (Latin: hebdomada, septimana) or of Sunday (dominica or the dominica) in the Latin translation, but only of the resurrection of Jesus and the church meeting "on a Sabbath," or "on the first Sabbath." Only in Mt 28,1b he should have better used "una" (a/one) according the Greek original text. Nevertheless, unlike some theologians of today, he was able to distinguish all these terms:

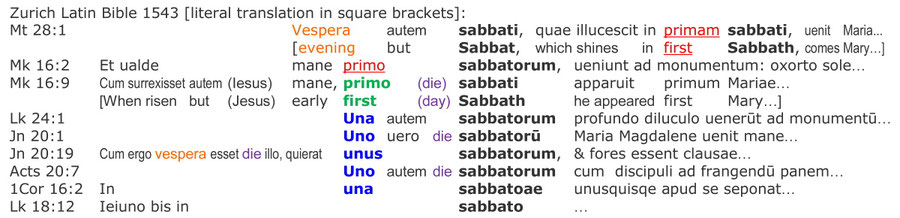

Zurich Latin Bible 1543

A new complete Latin edition of the Zurich Bible was printed (facsimile) in the Froschauer printing house in 1543. The editor was Konrad Pellikan (Biblia Latina - “Biblia sacrosancta Testamenti Veteris & Novi / e sacra Hebraeorum lingua Graecorumque fontibus consultis simul orthodoxis interpretib. religiosissime translata in sermonem latinum…“). The translation from Hebrew was done by Zwingli's friend and reformer Leo Jud (*1482, †1542). Since Jud died before completion, the work was finished by Konrad Pellikan. For the NT, the text of the Vulgate was not used, but a new translation in modern Latin was made. The NT was translated by Rudolf Gwalther according to the TR text published by Erasmus. This work could not prevail because it was inaccurate in many places and sometimes had superfluous and incorrect marginal notes. While this Bible mentions the Sabbath in all places, it is reinterpreted in the footnote that the word "sabbatorum" could supposedly mean the "week." This is clearly wrong. Neither the apostles nor Jerome (Vulgate) used the almost identical word for "week" in Greek and Latin (namely, hebdomadae) in the NT. The word sabbatorum (plural) does not mean "week," as evidenced by the use of the same word in many other verses. In Mt 28:1 the ordinary "sabbati" is mentioned twice (not sabbatorum) and in the other places the very same word "σαββατων" is used also in the basic text (Mk 16:2; Jn 20:1, 19; Acts 20:7; 1Cor 16:2). Moreover, sabbatorum is used in other verses in this Bible to describe a single Sabbath day, e.g., "die sabbatorū" (day Sabbath/s); Acts 13:14; 16:13) and no one questions whether "a Sabbath day" or "a Sunday" was actually meant in these verses. Thus, it becomes clear that the marginal notes are merely superfluous theological interpretations about content that is not in the Bible, but which the church desires. But on the other hand, these marginal notes are another proof that the word "hebdomadae" was commonly known, but just not written into the Bible (see week). Martin Luther did not agree with this translation and after receiving a copy as a gift, he wrote back angrily on August 31, 1543, that he did not want to have anything to do with "the false, seductive Zurich preachers," by which he meant some translators. Those translators who used this version of the Latin as a basis consequently had to adopt the same errors when translating it into another language. However, the Sabbat was preserved:

Beza Bible 1559

Theodore Beza (also Théodore de Bèze; *1519; †1605) was a Geneva reformer of French origin who worked closely with Calvin. A member of the Reformed Church, he produced critical text editions of the NT in which he twisted the content in the resurrection chapter toward church doctrine (facsimile). In the print edition of 1559, Beza writes about the introduction of the "hebdomada" (week) in a footnote to Lk 24:1 that this is justified by the authority of the Church. So it is church doctrines that were the deciding factor and not the Word of God per se. The literal Word of God was unimportant to Beza; he desperately wanted to see the word "Sunday" in the Bible. While the Greek basic text and the Latin Vulgate still clearly report about the appearance of the women "on a Sabbath" in all places, Beza brought the word "hebdomada" (week) into the Bible and he erased the "Sabbath" mentioned by God in the genitive singular and plural from the Bible for it. This is a NO GO. His work is clearly more inaccurate than many other Catholic editions of his time, for he retains the Sabbath only in Mt 28:1a. In all other verses he simply erases the same word from the Bible. He could not distinguish "one" from "first" (ordinal and cardinal number), nor did he note that while the word "week" appears in the OT, the Gospels specifically did not mention it. Beza was significantly in translations into French, English and German, which always proclaimed the unbiblical "first day of the week." Thus a church dogma moved more and more into the Bible. In 1580 he brought out a three-column Bible, with the basic Greek text, the Latin Vulgate and his new translation. In direct comparison, his errors are clearly noticeable. How illogical his translation is can be seen from the fact that in the Greek and Latin language no human being could have said "on a day", "on a Sabbath", "on the one of the Sabbaths" or "on the first Sabbath", because it would then automatically always mean "on a/first Sunday" or "on the first day of the week". Beza did not know God's calendar and did not know that the evangelists meant the first of the 7 weekly Sabbaths until Pentecost. The Reformed translation printed in Geneva, appeared in other languages of Europe besides Latin. It did a great damage in Christianity, because it was reprinted many times and in turn served as a basis for translation into other languages. Thus, the catastrophic translation errors were carried on to other regions of the world and the Word of God and Jesus was reinterpreted. Therefore, the sign of the Messiah (3 days and 3 nights) was also rejected and nobody believed Jesus anymore:

Biblia Políglota de Amberes 1572

The Spanish theologian Benito Arias Montano (Benedictus Arias Montanus, *1527; †1598; Wikipedia), son of a notary, knew ten languages. Therefore, the Spanish king Philip II (*1527; †1598) commissioned him to publish a multilingual Bible (Biblia Políglota), which he directed from 1568-1572 and had printed by Christophe Plantin (*1520; †1589) in Antwerp (facsimile; Polyglot Bibles). The seventh volume of the 1572 edition contains the NT (Nouum Testamentum graece: cum vulgata interpretatione Latina Graeci contextus lineis inserta: quae quidem interpretatio, cùm à Graecarum dictionum proprietate discedit... atque alia Ben. Ariae Montani... operâ è verbo reddita...). This is not the text of Jerome's Vulgate, but an improved version that corrects Jerome's errors and correctly translates the basic Greek text. Montanus was an expert, and his publication is still excellent today. Unlike many pastors of today, he was able to distinguish clearly between mia (one) and prote (first). He did not make mistakes. And he could also differentiate between the "week" and the "Sabbath" in all languages. The words "sabbati" and "sabbatorum" (Acts 13:14; 16:13) are the same as those used in all other verses in the OT and NT. Even Mt 28:1b is translated correctly by Montanus. Anyone who translates this text from Greek or from Latin into any other language can only conclude that the women came to the tomb "on a Sabbath" (in the singular) or "early on the first Sabbath" (mane prima sabbati). Thus, the Spanish king unconsciously supported the written proclamation of Jesus' resurrection "on a Sabbath morning," even though orally the day after (Sunday) was taught. This is the same written statement of both languages:

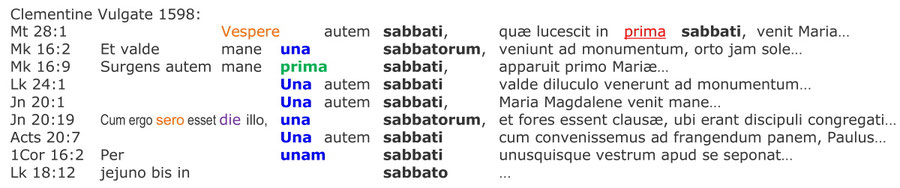

Clementine Vulgate 1592-1598

The Council of Trent (1545-1563; Wikipedia) determined that the Vulgate should be the sole translation of the Bible and the standard text for all churches worldwide. In 1590, under Pope Sixtus V (*1521; †1590; Wikipedia), a new official version appeared in Rome (the "Sixtine Vulgate"), but it was not yet satisfactory, whereupon another corrected work appeared (facsimiles) beginning in 1592. When Pope Sixtus died, his successor Pope Clement VIII (*1536; †1605, tenure 1592 to 1605; Wikipedia) ordered that all Bibles published during the previous two years be destroyed and issued a new Vulgate version, which was named the "Sixto-Clementine Vulgate" or "Clementine Vulgate." The first official edition appeared in 1592, the second in 1593, and the third in 1598, which was authoritative and generally accepted. It was probably the most famous Vulgate version in history. From 1641 it was also called "Biblia Sacra juxta Vulgatam Clementinam". A new edition, improved in spelling, appeared in 1914 (Hetzenauer Clementina Edition), the text of which served as the basis for the English-language Catholic Public Domain Version of 2009. The Sixto-Clementine Vulgate was officially used in the Catholic Church until 1979, when the Nova Vulgata (see below) was promulgated by Pope John Paul II. The Bishops' Conference of England and Wales also officially endorsed this Vulgate version, and in 2006 issued a revised Latin Bible that can be viewed free of charge on the Internet. The following is the text of the important Vulgate Clementine 1598, which tells the entire Christian world of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" (una sabbati), "early on the first Sabbath" (mane prima sabbati), and the gathering of the church "on a Sabbath" (una sabbati). The "Sabbath" is usually in the genitive singular, which is clearly defined in Latin and has nothing at all to do with Sunday or the week (see week). It is always only about the official Catholic message of the worldwide recognized Latin Bible, which contains in writing the resurrection Sabbath, even if from the pulpit orally the resurrection Sunday was preached:

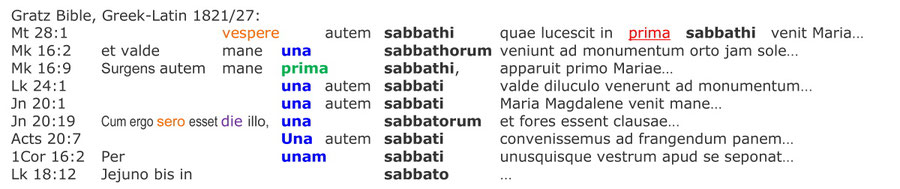

Peter Gratz Bible, Greek-Latin 1821

Professor Peter Alois Gratz (*1769, †1849; info and facsimiles) was one of the most important Catholic biblical scholars. Among his works was the bilingual "Novum testamentum graeco-latinum" of 1821, which was printed in Tübingen. Another version came out in Kupferberg near Mainz in 1827. It is interesting that the professor continues to use the text of the Vulgate, which has only small differences in the spelling of a few words. So it should have been clear to him that both the Greek and Latin Bibles tell only of the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath morning," although church doctrine speaks of Sunday. "Una autem sabbati" literally means "on a but Sabbath" and nothing else. Mark 16:9 is also child's play to understand, for Jesus appeared to Mary "early on the first Sabbath" (mane prima sabbati), a commonly known term for the first of the seven weekly Sabbaths that had to be counted each year until Pentecost (see God's calendar):

Nova Vulgata 1979

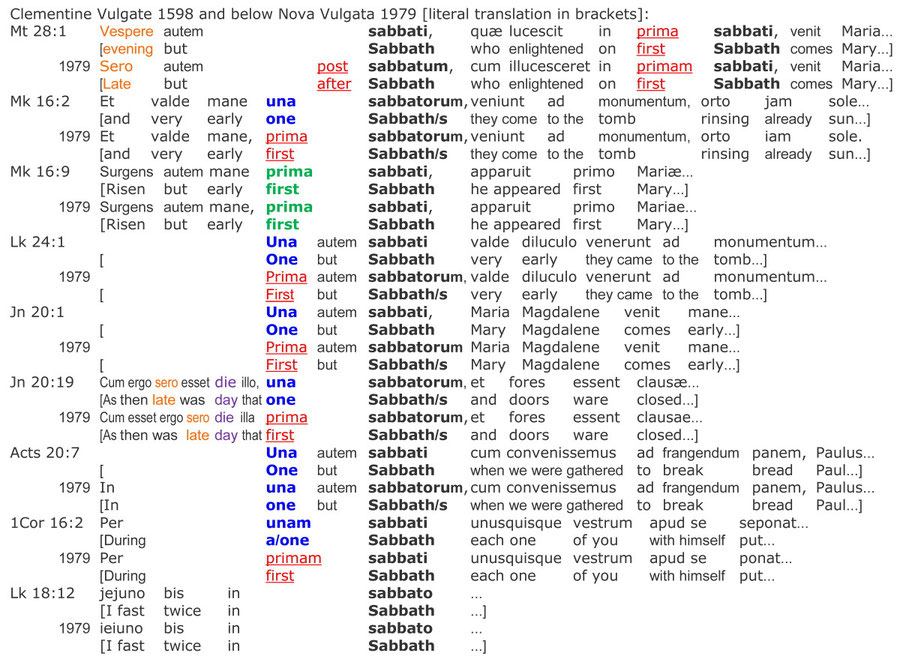

The Second Vatican Council (1962 to 1965) under Pope Paul VI commissioned a new edition of the Vulgate. Before the Nova Vulgata 1979 (facsimiles), the Clementine Vulgate from 1592 (Vulgata Clementina, see above) was the standard Bible of the Catholic Church. Under Pope John Paul II. (*1920; †2005) the first edition appeared in 1979, the second in 1986 (Wikipedia). The so-called Nova Vulgata is published on the Vatican's website. It rightly bears the name "New Vulgate", because instead of a correct translation of the basic Greek text, Catholic dogmas were updated and important statements of the Catholic Church Father Jerome were changed. While Jerome could still distinguish between una (one) and primo (first), the word una (one) suddenly no longer exists in the resurrection chapter of the Nova Vulgata. Instead, prima (first) always appears, although it should only be in Mk 16:9, since the Greek basic text and the Vulgate Hieronymi only speak of the "first Sabbath" here:

The following illustration shows the comparison of the two Catholic Vulgate editions from 1598 and 1979:

A comparison of the Nova Vulgata with Jerome's Vulgate and the original Greek text shows that two decisive changes were made:

1. "On" does not mean "after": Both the basic Greek text and the Catholic Vulgate of Jerome clearly speak of an event on the evening of a Sabbath in Mt 28:1a. But in the Nova Vulgata the word post (after) was added to the Bible. Thus an event that takes place ON a Sabbath day was postponed to an event AFTER that Sabbath. But if in Mt 28,1a the High Sabbath is meant, then the word "after" would even be correct in content, because there are 3 Sabbaths in the Passover week. But no Catholic learns this in the service:

2. "One" does not mean "first": God and the evangelists deliberately did not speak of the "first Sabbath" but of "one Sabbath." The only correctly translated passage is that in Mark 16:9, but since the Catholic Church is not familiar with the biblical feast days, it cannot know that the evangelists meant the "first Sabbath" of the 7 Sabbaths until Pentecost. Since there are always several Sabbaths in each Passover week, it is understandable why the apostles spoke of what happened "on the one of the Sabbaths". This referred to a very specific Sabbath, namely the small weekly Sabbath between the two high annual Sabbaths on the 15th and 21st of Nisan. This particular "one Sabbath" is called in Greek "the one of the Sabbaths," because there are three Sabbaths at Passover, and until Pentecost, according to Leviticus 23, there must even be seven Sabbaths counted each year between Passover and Pentecost. By the fact that the evangelists did not emphasize that it was a high Sabbath, it is clear that it must have been an ordinary Sabbath. Since no pope would accept the biblical resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath, and for him the phrase "earlyon the first Sabbath" was illogical, it was simply asserted that it supposedly meant the "first day of the week." The Nova Vulgata, however, in the resurrection chapter therefore added the word "prima" and erased "una," which had previously been in the Catholic Bible for 1,600 years. While Jerome (382 A.D.) and Pope Clement (1592) could still distinguish between cardinal (una) and ordinal numbers (prote), the Nova Vulgate can no longer:

Even the Nova Vulgata the "Sabbath" never means "week" or "Sunday"

The Nova Vulgata uses three grammatical Sabbath forms in the resurrection chapter, namely sabbatum, sabbatorum and sabbati. Now it is clear that in each case only the Sabbath can be meant. But the translators do not make it quite so simple for us. Some have made the claim that these three words can mean not only Sabbath, but also week or Sunday. This cannot be, for it would mean that people in the Latin language would never be able to say "on a Sabbath" or "on the first Sabbath," because then it would automatically have to mean "on the first day of the week" (see week) or "on a Sunday." Only in the imagination does "Sabbath" mean "week" or "Sunday." And those who want to argue here can first look at how the Nova Vulgate uses the same words in other places and all discussion ceases. It is always the Sabbath that is meant:

When the 10 Commandments were proclaimed, the Hebrew "Yom Shabbat" was translated as "diei sabbati" in the Nova Vulgate (Ex 20:8,11). It is clear that the Sabbath day must be meant and not the Sun-day. In the Greek text of the Septuagint the plural "day of Sabbaths" (ημεραν των σαββατων) was used for it. This was, according to ancient Greek grammar, something perfectly normal to describe a single Sabbath day in the singular. In the basic Greek text, the samme plural σαββατων appears 11 times in the NT. It is translated in the Nova Vulgate in the singular as sabbatum (Mt 28:1a), sabbati (Mt 28:1b; Lk 4:16), and plural sabbatorum (Mk 16:2; Lk 24:1; Jn 20:1, 19; Acts 13:14; 16:13; 20:7; Col 2:16). There are some people who say that sabbatorum could supposedly mean "week." But as has been proven many times, "Sabbath" is a clearly defined term (see Sabbath) and has been so not since yesterday, but for several thousand years, more precisely since creation. Moreover, sabbatorum also appears in 4 other places (Lk 4:16; Acts 13:14; 16:13; Col 2:16) and is translated as "on the Sabbath day" in the singular in all the world's Bibles. Examples: In Acts 13:14 we find "die sabbatorum" (day Sabbath) and in Acts 16:13 "die autem sabbatorum" (day but Sabbaths). In Col 2:16 "diei festi aut neomeniae aut sabbatorum" (day feast or new moon or Sabbath). In Lk 4:16 the Nova Vulgate translates the plural "τη ημερα των σαββατων" (on the day of the Sabbaths) in the singular as "die sabbati" (on the day Sabbath). It is pure interpretation to claim that in these passages the "Sabbath" is meant, but in the passages of Jesus' resurrection, of all things, the "Sunday" is meant. This is a terrible change of the Word of God. And what if God really meant the Sabbath? Many Catholic translators did not make this mistake and produced correct Bibles (examples).

Mark 16:9 also makes it clear that it must have been a specific Sabbath, since it is singular: "Surgens autem mane, prima sabbati" ("risen but early on the first Sabbath"). But if the Pope does not know God's Luni-Solar calendar and the calculation of God's feasts, and uses only his solar calendar (with quite different formerly pagan feast days), then of course he cannot know what the "first Sabbath" is that Mark mentions in Mark 16:9, because the Pope knows only the "first Sunday in Advent." Why, then, does he not know that God describes the first Sabbath and the seventh Sabbath until the Feast of Pentecost in Leviticus 23? The fact is and remains that the Pope could never find the corresponding Greek and Latin words for "Sunday", "week" or "after the Sabbath" in the Resurrection chapter, because both languages and also many translations from the Vulgate speak of the Resurrection Sabbath or even Resurrection Saturday. This is the historical truth, the correctness of which every Christian can check for himself in just a few minutes. No one has ever found an alleged Resurrection Sunday in the Bible. The "Resurrection Sunday" is just a theological claim in modern Bibles that do not take the basic text of the Bible seriously and translate it as they would like it to be, but not as God said it should be. Soon all these people and the many pastors (who seduce their entire church to Sunday) will stand before God and Jesus, then they will have the opportunity to show Him the Sunday in the Bible, because Jesus will show them the Resurrection Sabbath, not just once, but exactly 7 times in the Resurrection chapter of the NT.

The "week" in the Nova Vulgata

When God explicitly mentions 7 times that the day Jesus was resurrected has the name "Sabbath", He means the Sabbath. God did not speak of "die dominus", "die Solis", Kyriake or "primo die hebdomadae". No man can plausibly explain why God should mean Sunday when He speaks of "a Sabbath," His own day. No one on earth has to get so complicated and talk about the "Sabbath" when he means the "week" or the "Sunday." People (and even children) have always been able to distinguish clearly between the thee terms. Only the theologians cannot.

The Nova Vulgata knows the Latin term for week (hebomada) very well and mentions it many times in the Old Testament (OT). This is correct, for it is nothing other than the corresponding Greek translation for the similar-sounding Hebrew word ebdomadas, which means sevenness (a unit of 7 days; see week). Some examples from the Nova Vulgata: "hebdomade una" (one week, Dan 9:27a), "duabus hebdomadibus" (two weeks, 3Mo 12:5), "Sollemnitatem Hebdomadarum" (Feast of Weeks, Ex 34:22; Num 28:26; Deut 16:16; 2Chron 8:13), "diem festum Hebdomadarum" (day festival weeks, Deut 16:10), "Imple hebdomadam hanc" (fulfill this week, Gen 29:27), "hebdomada transacta" (wedding week, Gen 29:28), "tribus hebdomadis" resp. "tres hebdomades" (three weeks, Dan 10:2,3), "septem hebdomadas" (seven weeks, Lev 25:8; Deut 16:9), "hebdomades septem" (7 weeks, Dan 9:25a), "hebdomadae septimae" (seventh week, Lev 23:16), "hebdomades sexaginta duae" (62 weeks, Dan 9:25b), "Et post hebdomades sexaginta duas" (and after 62 weeks, Dan 9:26), "septuaginta hebdomades" (70 weeks, Dan 9:24), "in dimidio hebdomadi" (in the middle of the week, Dan 9:27b). Of particular interest is Lev 23:15, for here "Sabbath" and "week" appear in one sentence: "Numerabitis vobis ab altero [count from the other] the sabbati [day Sabbath], in quo obtulistis manipulum elationis [as you offer the sheaf as a wave offering], septem hebdomadas plenas [7 weeks whole]." In 2Chron 23:8, the Sabbath and once the week are found together twice in one sentence: “qui veniebant sabbato“ [which arrived on the Sabbath], “qui sabbato egressuri“ [went out on the Sabbath] und “per singulas hebdomadas“ [through each week]." It is the phrases with both words together (Lev 23:15; 2Chron 8:13; 23:8) that prove that even the Nova Vulgate can differentiate between "Sabbath" and "week" when translating the basic Greek text. Importantly, in the NT of the Nova Vulgate, "week" is rightly not found at all. Even the phrase in Lk 18:12 "ieiuno to in sabbato" (I fast twice on the Sabbath) has been correctly translated.

Conclusion

The Catholic Bibles have shown us the resurrection Sabbath, which has been in the Latin Bibles since the first Latin translation (Vetus Latina and Vulgate) until today. We can be very grateful to the Catholic Church, because its Latin translation of the basic Greek text has been carried out very well in very most verses. It must not only be criticized, the positive works must also be mentioned. Thus, numerous Catholic Bible translators have spoken of the coming of the women to the tomb "on a Saturday morning" or "on a Sabbath morning" just as it was beginning to be light (see Old Bibles). Even the Nova Vulgata, on the Vatican websites, proclaims to this day the resurrection of Jesus "on the Sabbath," since it mentions the "first Sabbath" in all verses. But this never means "on the first day of the week". Who now knows that this is (according to God's calendar) the first Sabbath of the 7 Sabbaths until Pentecost, understands the statements of the Bible without problems. Although the Church has always preached orally the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sunday", their own Bibles have always said the resurrection of Jesus "on a Sabbath" or "on a Saturday". This is a historical fact that can be easily and quickly proven. This is the age-old Catholic teaching that its own Bible tells of the Resurrection Sabbath, even though orally the day after, the alleged "Resurrection Sunday" was preached. To achieve this Sunday goal, of course, the sign of the Messiah (3 days and 3 nights) was also denied and no one believes the words of Jesus anymore. The following table shows the counting of the 7 Sabbaths until Pentecost in modern times. Selected were the years in which the 14th Nisan (day of crucifixion) falls on a Wednesday according to the Jewish calendar, which is very often the case, namely about every third year:

All this is so easy to understand and so extremely clearly described in the Bible, why don't the Pope and the many evangelical pastors in the USA understand it? They rather defend the Pope and his calendar with his own feast days, but reject the calendar of God with the feast days of God, as well as deny the sign of the Messiah, the most important sign in the history of the universe. And there will be no more important sign in all eternity.

Numerous Bibles in many languages teach the resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath morning:

7. Many old Bibles proclaim the resurrection of Jesus on a Sabbath or Saturday morning

7.1 Greek Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.2 Latin Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.3 Gothic Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.1 German Bible manuscripts show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.2 German Bible prints 1 (before Luther) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.3 German Bible prints 2 (since Luther) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.4 German Bible prints 3 (since 1600 to 1899) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.4.5 German Bible prints 4 (since 1900) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.1 English Bible manuscripts show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.2 English Bible prints 1 (from 1526 to 1799) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.3 English Bible prints 2 (from 1800 to 1945) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.4 English Bible prints 3 (from 1946 to 2002) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.5.5 English Bible prints 4 (from 2003) show the Sabbath resurrection

7.6 Spanish Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.7 French Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.8 Swedish Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.9 Czech Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.10 Italian Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.11 Dutch Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

7.12 Slovenian Bibles show the Sabbath resurrection

"Prove all things; hold fast that which is good. Abstain from all appearance of evil"

(1Thess 5:21-22)

"Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them"

(Epheser 5:11)